City policies typically focus on managing urban systems and functions, like transport networks and housing markets, or pursue outcomes, measured in social, environmental or economic terms. Cities also have a cultural dimension that is harder to quantify and integrate into policy frameworks and governance arrangements. Ultimately, cities exist as physical places that are imbued with layers of meaning, only some of which are addressed in the traditional domains of urban policy.

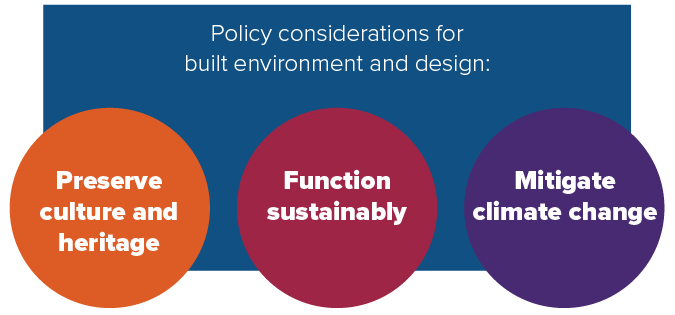

This Brief on ‘Built Environment Design’ aims to identify the ways the physical built environment and its cultural meanings are addressed in urban policy, and to consider the role of design and design governance in Australian cities. International approaches and perspectives are also considered.

Building culture

Historically, the design of cities and of major civic buildings has been among the foremost considerations of regimes that have sought to influence the development and governance of cities. Often, civic design and architecture has served to support ideologies and to entrench the power of military and economic elites. Since the so-called ‘failure’ of modernist technocratic planning, design has played a relatively marginal role in urban policy and the production of the built environment. The exception to this has been major ‘city-branding’ projects, where ‘iconic’ buildings or major renewal projects are often used to define and promote a city’s global image.

Through the Davos Declaration (2018), European governments have sought recently to redefine and promote the concept of Baukultur with the acknowledgement that, “the cultural value of the quality of the built environment as a whole, with cultural heritage and contemporary creation being understood as a single entity, is hardly ever defined as a political goal.” The ambition is that jurisdictions would formulate cultural expectations regarding the preservation, design and creation of the built environment “for the common good.”

Most capital city strategic planning policies in Australia contain objectives about built environment quality and promote the role of design in achieving this. Plan Melbourne 2017-2050 calls for ‘a distinctive and liveable city’ among its principle objectives. Similar ideas are contained in A Metropolis of Three Cities under the objective that Sydney be ‘a city of great places.’ In both these Plans, ‘quality design and amenity’ and a ‘well-designed built environment’ are associated, respectively, with these aims.

The metropolitan planning strategy aims to achieve and promote design excellence by ensuring high quality urban design in the built form of Melbourne, and by respecting heritage in urban renewal projects.

Urban design and heritage

Australian governments introduced heritage legislation in the 1970s and heritage regulation operates across all levels of government. Current urban policies refer to heritage planning and urban design to varying degrees, within the frameworks guiding the development of existing urban areas in Australian cities. The integration of heritage planning and urban design in urban policies is related to improved environmental, health and social outcomes, as well as to cultural objectives. These topics feature strongly within Plan Melbourne 2017-2050. The metropolitan planning strategy aims to achieve and promote design excellence by ensuring high quality urban design in the built form of Melbourne, and by respecting heritage in urban renewal projects.

Design governance

The role of design in planning remains contested. Several states define and promote urban design principles or protocols, some of which are incorporated into planning regulations. In the twenty-first century, residential apartment development became a significant driver of physical change in the built environment of major Australian cities and has prompted the introduction of design standards and design review processes into planning.

NSW was the first to introduce a comprehensive suite of such policies (under SEPP 65 in 2002—identified as national best practice in the COAG Review of Capital City Strategic Planning Policies in 2011), although Urban Design Principles very similar to the Design Principles of SEPP 65 have existed in the Victoria Planning Provisions since 1996. Design WA, which aims to improve design outcomes in development, also had apartments as a focus during Stage One of its implementation.

Today, most Australian states and territories have a government architect, in a non-statutory role, to advocate for built environment design quality in government projects and processes. In some states, this function is further supported by policy. Western Australia has had a Built Environment Design Policy since 2012 and New South Wales has an integrated design policy, Better Placed. In some major urban centres, Design Excellence guidelines and competition processes are in place as a mechanism to drive the quality of built outcomes in certain circumstances.

Environmentally sustainable design

The design of the built environment has an important part to play in the transition to net zero emissions, and meeting Australia’s commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement. A high proportion of Australia’s emissions are associated with infrastructure projects. The delivery of new infrastructure, and the renewal of existing transport, energy, water, communications and waste infrastructure requires engineering and design solutions that focus on the selection of materials, minimising waste, and energy conservation.

Housing design and retrofitting is also important in facilitating the shift to low-carbon living. Residential and commercial buildings comprise around one-fifth of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions. While energy efficiency and water management are regulated under national and state building codes, the Green Building Council of Australia advocates inclusion of a single star rating system for homes, commercial and institutional buildings. New technologies focused on energy, water and waste systems in homes and other buildings can have beneficial impacts on household environmental sustainability. The building industry has an important role to play in delivering energy and resource efficient buildings and implementing low carbon building practices. The use of local supply chains for materials, energy efficient materials and passive design principles are key to minimising environmental impact.

Urban design and planning can also provide for active transport solutions, the preservation of green space, and promotion of architectural responses to the challenge of improving environmental sustainability. The redesign of cities and buildings to accommodate energy efficiency practices, as well as implementing engineering and architectural design solutions, will be essential in the transition to one planet living.