Can welfare reform really give consumers housing choice?

22 Nov 2022

In countries such as the UK, the USA and Denmark there have been moves towards more individualised packages of support for people who require assistance due to older age, disabilities, homelessness, health issues and a range of other vulnerabilities. The aims are to give people greater control over their own lives; promote personal responsibility; develop a diverse range of services which can meet needs in a more customised way; diversify service provision through the involvement of a range of private and not-for-profit providers; and make government assistance more cost-effective.

In Australia, promoting consumer choice (‘individualisation’) is featured in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) Act. The premise underlying 'individualised forms of welfare assistance' is that:

- individual welfare recipients are able to choose what type of support they get, who provides the support, and even what mix of support they get (e.g. more housing assistance and less of some other benefit, or vice versa)

- it promotes personal responsibility and builds self-capacity in the recipient

- it promotes a diverse range of services provided by a range of private and not-for-profit providers and makes government assistance more cost-effective

- it promotes 'social development that underpins the ability of individuals to properly engage in the real economy and make meaningful choices'

- there is concern that 'long term welfare dependence saps people of motivation and erodes personal responsibility and individual capacity'.

For people on government benefits and low incomes there are shortages of affordable rental accommodation and long waiting lists for public housing. Demand for affordable dwellings can only be realised if there is an effective supply-side response, that is, forms of housing assistance given to providers of housing to help increase the quantity of housing.

There is a real question of how can demand-side measures (i.e. forms of housing assistance given to consumers of housing to help them meet their housing requirements) that promote consumer choice be reconciled in a housing system that requires increased supply?

Consumer choice in housing

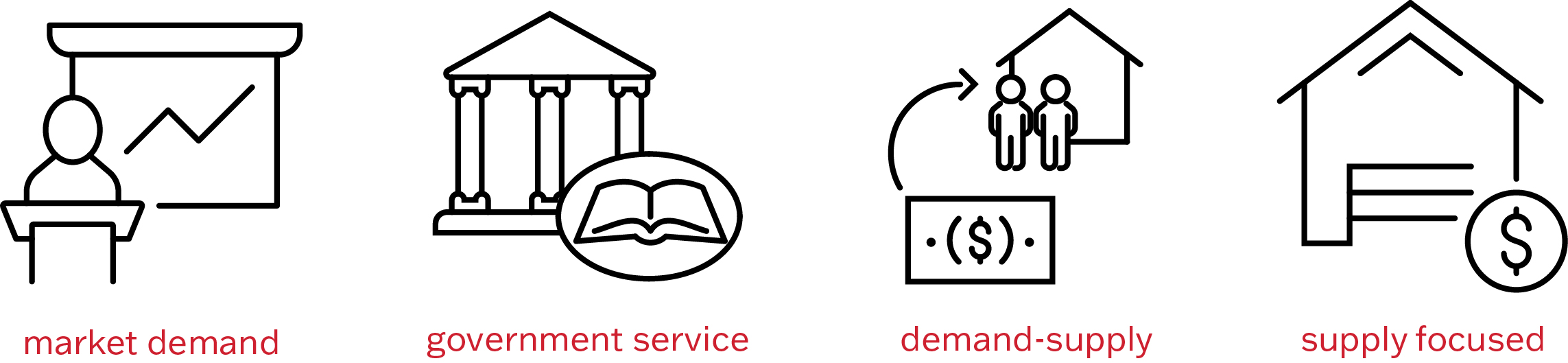

There are four different policy approaches to addressing the issue of promoting consumer choice in housing:

- Market demand – to provide funds or other resources (e.g. CRA or First Home Owners Grant) to provide low-income households with increased purchasing power in the market. There has been a criticism of in that subsidies have not been able to keep track with rising housing costs in inner and middle suburbs of major cities, thereby reducing the degree of individual choice.

- Government service – to create market signals and quasi-choices in the design of government services (e.g. choice based letting in the allocaton of public housing). An example is seen in the UK where social housing was allocated using choice-based lettings. When social housing dwellings become vacant they are advertised so that eligible registered applicants can ‘bid’ for (i.e. express an interest in) renting the property. The intention is to empower clients to make choices about their housing and therefore increase their satisfaction with it.

- Demand-supply – to marry increased consumer choice with increased housing supply, such as by limiting government Shared Equity schemes or the First Home Owners Grant to newly built dwellings only. An example is the Western Australian Government-backed Expression of Interest (EOI) shared equity initiative that is directly linked with the building of new dwellings. These properties were then made available for eligible low income buyers through The Shared Start loan.

- Supply focused – to increase consumer choice by increasing the supply of affordable dwellings, such as through inclusionary zoning and/or developer contribution in planning schemes to ensure the building of new affordable housing.

What is needed

In a context of constrained housing supply the first two approaches—market demand and government service—have limited probabilities of success as they each rely upon having an adequate supply of houses in places where people want to live for the consumer choice to be realised. Ultimately, targets to increase the number and variety of homes affordable to households on low incomes will be the basis of any individualisatised welfare reform.

In 2017 the Productivity Commission tackled the topic of welfare choice and promoted ‘a single system of financial assistance that is portable across rental markets for private and social housing ... One, it would enable a person to choose where they live based on their preferences — their access to financial assistance (and tenancy support services) would ‘follow them’. Two, it would address current inequities by targeting the type and amount of financial assistance a person receives to their circumstances, rather than the type of housing they live in.’

However, underpinning the Productivity Commission’s response is that there really is a need to build more dwellings affordable and suitable for people on very low incomes (including for people on disability support pension which may require specifically designed housing that is unlikely to exist in the private rental market). AHURI research on the topic revealed that ‘it is difficult to exercise choice in the private rental market due to shortages of affordable accommodation. Only government investment in addressing supply shortages will increase the choice for very-low-income and vulnerable households.’