When compared with other client groups who accessed help from SHSs, people escaping DFV were more likely to be in private housing at the start and end of SHS support. This may be that they were more likely to be in housing when they first presented to the SHS, ‘short-term accommodation was their greatest housing need which is in contrast to other groups which often needed long-term housing the most.’

What is domestic and family violence?

Domestic violence refers to acts of violence that occur between people who have, or have had, an intimate relationship, while family violence may occur between family members, including child/parent/elder abuse, or through foster care relationships.

While domestic violence is most commonly perpetrated by men against their female partners, it also includes violence perpetrated by women against male partners and violence within same-sex relationships.

How does DFV affect housing outcomes

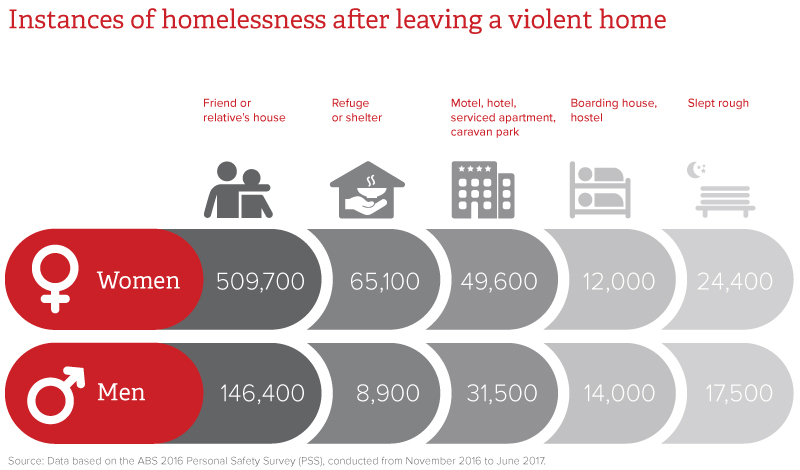

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016 Personal Safety Survey reveals that around 1.26 million Australian women and 370,000 Australian men had, at some point, ended a married or defacto relationship with a partner who had been violent towards them. Of those who moved out of the home, many effectively became homeless for a period of time.

Of the approximately 756,800 women who moved out, there were 509,700 instances of staying at a friend or relative’s house; 65,100 instances of staying in a refuge or shelter; 49,600 instances of staying in a motel, hotel, serviced apartment or caravan park; 12,000 instances of staying in a boarding house/hostel; and 24,400 instances of sleeping rough (e.g. on the street, in a car, in a tent, squatted in an abandoned building).

For men who moved out (approximately 223,400 men), there were 146,400 instances of staying at a friend or relative’s house; 8,900 instances of staying in a refuge or shelter; 31,500 instances of staying in a motel, hotel, serviced apartment or caravan park; 14,000 instances of staying in a boarding house/hostel; and 17,500 instances of sleeping rough.

Supporting access to private rental housing for people escaping family violence

For people escaping DFV, having fast access to secure, stable housing is critical to promote safety and wellbeing, including for children. However, for many recipients of SHS assistance there is little change in their housing situation over the time in which they receive support.

One option is specific subsidies or programs available to assist people escaping DFV to access private rental housing. These programs may be transitional housing programs or programs that help people escaping DFV stay in a new home for longer time periods.

Transitional housing is often supported short-term accommodation that is very temporary in nature, and tenants must work with their support provider to apply for long-term housing such as social housing or private rental housing. At the end of the subsidy period clients may not be eligible for further program support and will need to transition, if necessary, to other forms of support such as Jobseeker, disability support pension or Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA).

Examples of subsidies or programs include the Rent Choice Start Safely subsidy in NSW and the Rapid Rehousing head-leasing program in Tasmania.

The Rapid Rehousing program provides people affected by family violence with transitional accommodation in the private rental market at a subsidised rent. It is administered through Housing Tasmania and involves a Community Housing Provider taking a one, two or three year lease on a suitable furnished property in the private rental market, and then sub-letting the property to an eligible tenant who is escaping DFV. As the properties are already furnished the person escaping DFV is able to move quickly into their new home and not have to worry about sourcing furnishings and appliances at a time when they are facing considerable emotional stress.

Initially the tenant is given a short, three month or less lease, but this can be extended up to a maximum of one year. Tenants pay a rent that is subsidised so that they pay a maximum 30 per cent of household income.

The Community Housing Provider receives $13,000 from the Government per approved property per year to assist with tenancy management costs, including subsidised rent and waiving of bond payments; furnishings and appliances; fixed water and electricity costs and connection fees; and any necessary security of safety upgrades.

The Rapid Rehousing programs features exit planning with the tenant and government entities to ‘ensure that long term housing needs are met and to determine ongoing support needs (if any)’.

Although Rapid Rehousing can be considered as a longer-term transitional accommodation option, if tenants are able to, they may take over the lease (paying market rent) for the property long term and deal directly with the landlord or agent.

Support programs such as Rapid Rehousing are valuable in certain markets, giving women a degree of choice and flexibility and access to a greater portion of the market than they would otherwise have had. However, in markets where rents are high and climbing, the assistance may not be enough as once the subsidised period ends, the unsubsidised rent may become unsustainable.