A campaign called ‘The Home Stretch’, that aims to reduce homelessness by increasing the age young people can stay in foster care to 21, has been successful in South Australia and Tasmania (both have announced plans to extend care) and is now working towards the same reform in Victoria and NSW.

Research shows that young people leaving out-of-home care suffer high levels of homelessness. Out-of-home care is the placement of a child (aged 0 to 17 years) who is unable to live with their parents or other primary caregiver with alternate caregivers on a short- or long-term basis as decreed by state or territory authorities.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies identifies five types of out-of-home care:

- Residential care – placement in a residential building with paid staff

- Family group homes: homes for children provided by a department or community-sector agency, which have live-in carers who are reimbursed and/or subsidised for the provision of care

- Home-based care – placement in the home of a carer who is reimbursed for expenses for the care of the child. There are four categories of home-based care: relative or kinship care; foster care; third-party parental care arrangements; and other home-based, out-of-home care

- Independent living – includes private board and lead tenant households

- Other – placements that do not fit into the above categories and unknown placement types. This may include boarding schools, hospital, hotels/motels and the defence forces.

The 2009–10 Intergenerational Homelessness Survey of 586 participants revealed that 18.5 per cent of homeless adults had been placed in foster care (out-of-home care) at least once before they turned 18.

In the year to 30 June 2017 government agencies had placed 47,915 children and young people (i.e. aged 17 years and under) in formal out-of-home care because they were deemed to be at some level of risk due to their home circumstances. In that same year, 3,160 young people aged 15 to 17 were discharged or, having turned 18, were allowed to ‘age out’ of the out-of-home care system. For those turning 18 with no family support and no economic support from foster families (who no longer receive support payment once a child in their care turns 18) the transition to ‘independence’ is often one into homelessness.

AHURI research published in 2010 interviewed 77 young people aged 18 to 25. Of those interviewed, only 18 were classified as successfully leaving care; 59 had a volatile experience either during and/or after leaving care, and of those, 20 were homeless at the time of the research. None of the successful leavers were homeless at the time of the research, although they may have experienced homelessness at some time since leaving care.

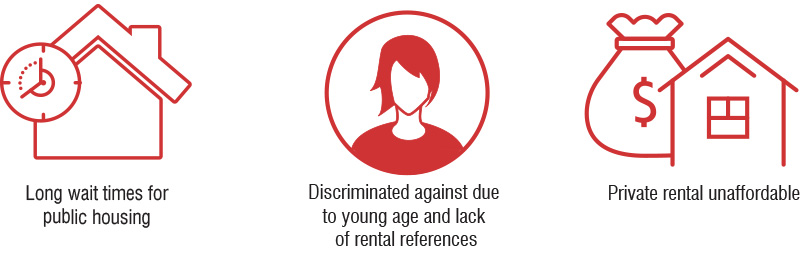

Figure 1: Reasons for homelessness amongst young care leavers

The research identified three main reasons for the high level of homelessness for young care leavers:

- many were discouraged by the long wait times for public housing and the complicated application process, and were often removed from public housing waiting lists due to their high mobility and loss of contact with the appropriate housing office

- they felt that they were discriminated against in the private rental sector because of their age and a prevailing view that young people were irresponsible tenants. They also lacked rental references

- private rental was not affordable for many care leavers, and they did not have the resources to secure and maintain housing even if it were available.

After they had left care, the ‘successful leavers’ had reliable and consistent social connections who assisted them to access and maintain accommodation; used stable housing as a base from which to start engaging with employment, training and education opportunities; and had someone to fall back on if problems emerged. Indeed, the key to accessing and maintaining independent housing was often the provision of meaningful support, both emotional and material, including professional support.

For those turning 18 with no family support and no economic support from foster families... the transition to ‘independence’ is often one into homelessness.

Although legislation exists in both Victoria and Western Australia (where the 77 interviews with young care leavers were conducted) requiring all young people over 15 to have a leaving care plan, only one-quarter of those in the study recalled having such a plan. This suggests that a meaningful plan must offer a plan of action that specifies how a care leaver can obtain housing, training, employment, state support, health and other services. In addition, each plan must be supported by case workers, with periodic active follow-up throughout the leaving care process.

To further support young care leavers with housing, the research proposed a form of Secure Tenancy Guarantee Scheme that provides a rent subsidy to all young people leaving care so that they pay no more than 25 per cent of their income for their housing up to the age of 25. By being tenure neutral, the scheme would give young people more reasonable accommodation choices (e.g. stay on with a foster carer, move into public housing, stay in supported housing or find appropriate private rental) and help them to avoid poor quality accommodation that, due to affordability or availability issues, is far from educational and employment opportunities.