What is the difference between social housing and affordable housing - and why do they matter?

As Australia is gripped by a worsening housing and rental crisis, discussion has centred on the urgent need for more social and affordable housing. While they are terms often used together, (and could be easily mistaken as interchangeable), ‘social housing’ and ‘affordable housing’ are two different things. This AHURI brief explores: Just what is social housing, what is affordable housing, and why are they both so important for our market-based housing system?

28 Feb 2023

What is social housing?

Social housing is government subsidised short and long-term rental housing. In Australia in recent decades, it has mainly been available to people on very low incomes, and who often have experienced homelessness, family violence or have other complex needs. Social housing is made up of two types of housing:

- public housing, which is owned and managed by State and Territory Governments, and

- community housing, which is managed (and often owned) by not-for-profit organisations.

Social housing differs from private rental in that housing is allocated according to need, rather than by households competing in a market, and from emergency accommodation in that it provides longer term and secure rental housing.

Social housing provides housing for people who are very unlikely to afford private rental market rents in most areas or who will find it difficult to be accepted into private rental due to a need for medical, age-related or other forms of support. It provides people with homes where they can live with dignity and as comfortably as possible, and, as an added benefit for the wider society, helps reduce people’s use of expensive health and judicial services. For some people, social housing provides a place where they can rebuild their lives, acquire education skills and access employment opportunities.

Rents for social housing are set with different considerations in mind, depending on whether the dwellings are public housing or community housing. Public housing rents are calculated at 25 to 30 per cent of the household’s income (depending on household income and composition). If, for larger households, the 25 to 30 per cent rent level exceeds the local market rent for that property, then the local market rent is applied.

For community housing, the 25 to 30 per cent of income rent rate (once again, depending on household income and composition) is applied only to very low-income tenants. As community housing tenants are also eligible for Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA), that subsidy will be paid to the community housing provider, resulting in a rent that may approach local area market rents. The Australian Tax Office has ruled that, as charities, GST will not apply to not-for-profit community housing providers that charge rents that are less than 75 per cent of local market rents. As a consequence, in such situations community housing providers charge rents at 74.9 per cent or below of market rents.

How much social housing does Australia need?

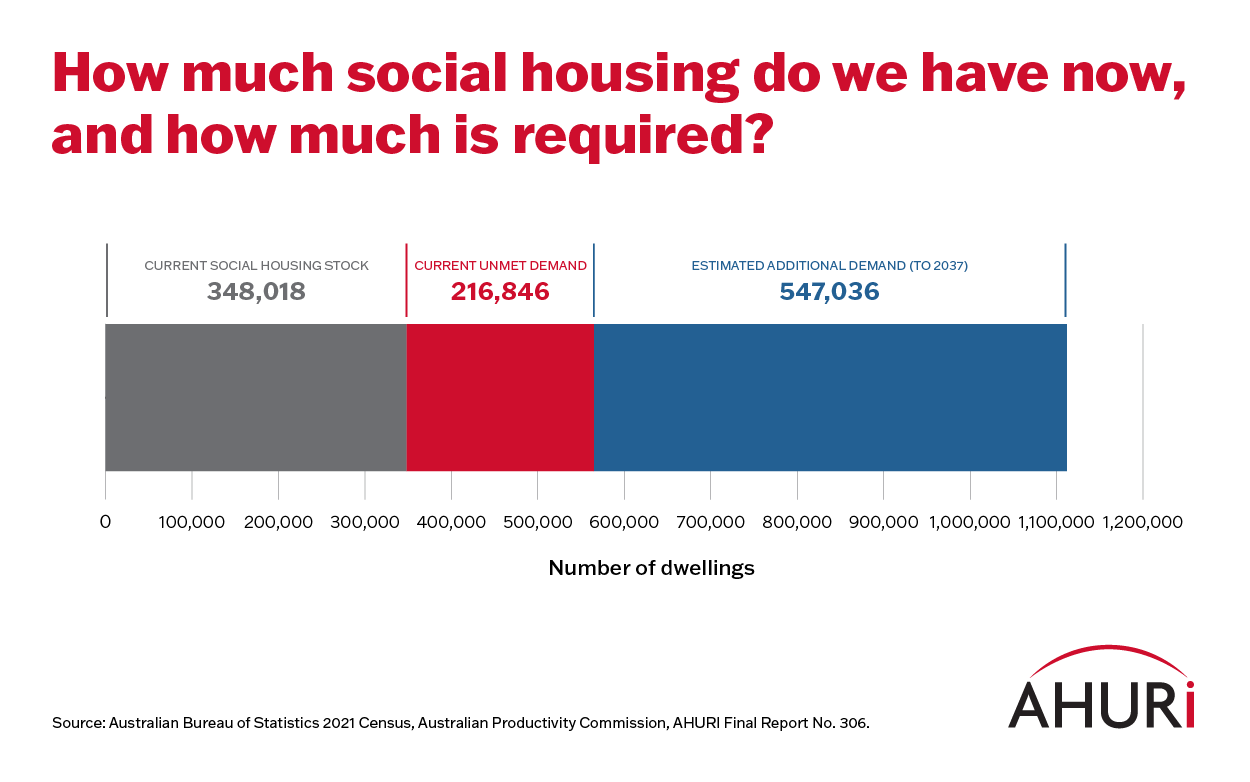

Determining just what is the right level of social housing in a healthy housing system is complex. While the 2021 Census recorded there were almost 350,000 social housing dwellings across Australia (just shy of 4% of the number of all households), at the end of June 2021 there were another almost 165,000 applicants on the waiting lists for public housing, more than 40,000 applicants for community housing and just over 12,000 applicants for State owned and managed Indigenous housing (SOMIH). If we add together all the households on the waiting list and those already in social housing, we find that over half a million (close to 565,000, or just over 6 per cent) Australian households were living in, or had requested to live in, a form of social housing. AHURI research has projected growth in demand for social housing to the year 2037, estimating that over 1.1 million social dwellings will be needed by that point.

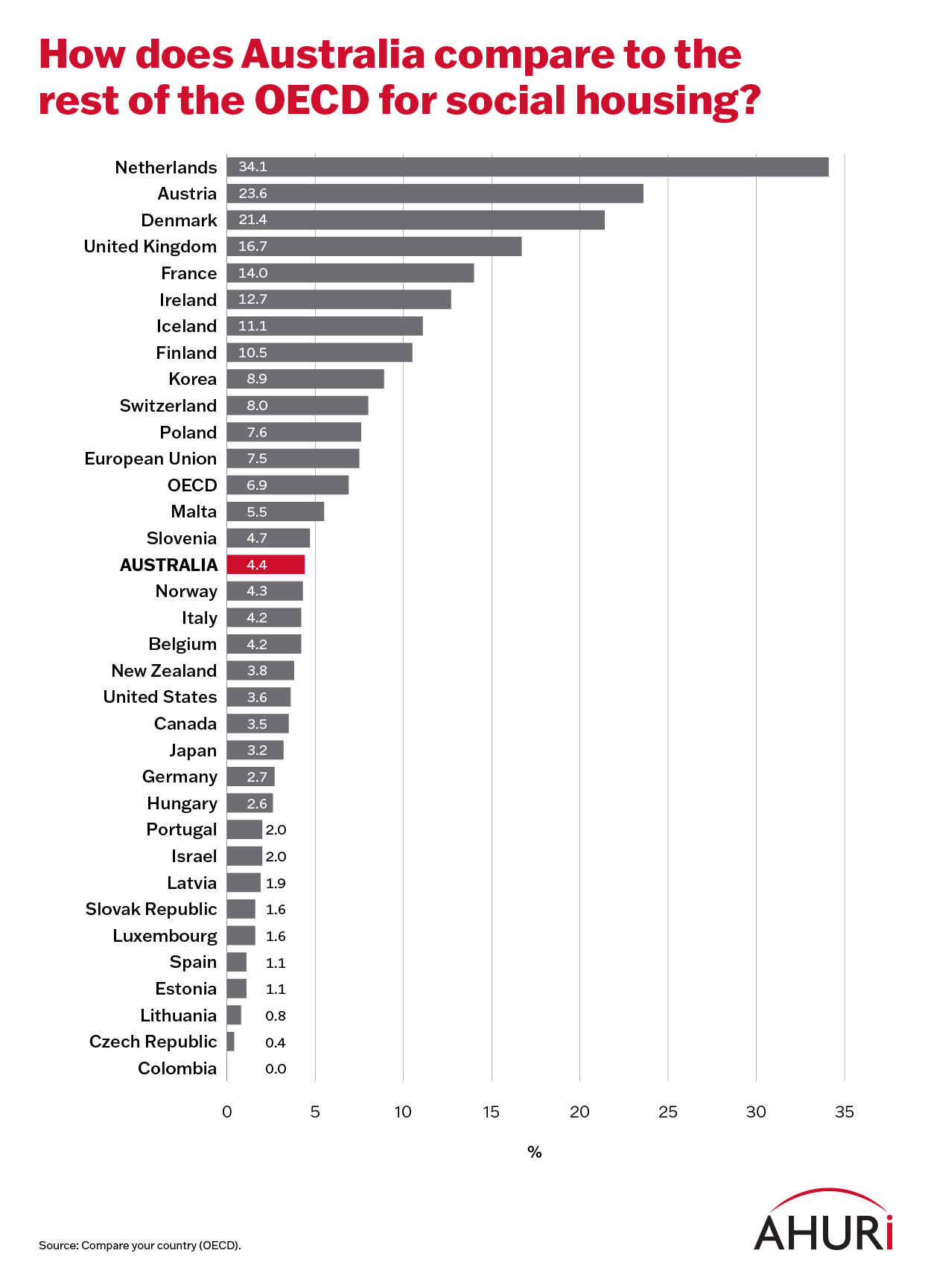

Australia's level of social housing in 2020 is low in comparison to the UK (17%) and countries within the European Union (with an average of almost 8%, but varying from 34% in the Netherlands to less than 1% in Lithuania) but is comparable to culturally similar Canada, New Zealand and the US (all just under 4% respectively).

State and territory governments are responsible for supplying public housing and a number have schemes in place to increase the number of dwellings (including working with community housing providers to increase supply). In August 2022, Federal Minister for Housing Julie Collins estimated that state and territory commitments totalled 15,500 new social and affordable dwellings. Since then there has been a stream of new commitments from the states and territories, and more are anticipated in the coming months.

The Federal Government has also announced measures to increase the supply of social and affordable housing through the Housing Australia Future Fund, which will fund the build of 20,000 social dwellings by 2029.

While the increase in social housing dwellings is to be applauded, Australia needs a massive and sustained increase in the supply of social housing if there are going to be enough homes for people on lower incomes.

What is affordable housing?

Defining what is ‘affordable housing’ is a much less precise exercise, as in Australia it doesn’t have a common meaning across jurisdictions and government programs.

For some jurisdictions, 'affordability’ may be defined based on a household’s ability to pay (determined by the household’s income), for others it may be defined as a housing rent or price that is lower than the prevailing local market rate. Some jurisdictions refer to rental housing only, for others it includes home ownership as well as rental.

For example, both the NSW and Victorian Planning Departments frame affordable housing in relation to a household’s income and consider that it is for very low to moderate income households. However, the NSW Department of Planning considers affordable housing to be ‘rental housing for members of the community who may not be able to afford to rent in the general market’; in contrast, the Victorian Planning and Environment Act states that affordable housing is housing that may be purchased or rented. The Victorian Act also states that affordable housing includes social housing (i.e. public housing and community housing), and housing for people on moderate incomes.

Previously (in 2005) a meeting of Australian Housing, Local Government and Planning Ministers had described affordable housing as ‘housing which is affordable for low and moderate income households across home ownership, private rental as well as public rental tenures … The benchmark for affordability is 25 to 30 per cent of the income of these target groups.’

The now discontinued National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS) considered affordable housing as having rents lower than the prevailing local market rate, with the Scheme capping rents at 20 per cent below market rates to eligible tenants for a 10-year period. While this was a welcome form of assistance, depending on location, the reduced rents were not always 'affordable' in absolute terms. In higher rent regions (such as capital cities and some regional coastal cities) low-income households receiving such assistance to make their housing ‘affordable’ could still be in housing affordability stress (i.e. paying more than 30% of income in housing costs). In other words, housing may be considered affordable when compared to the market rent, but it may not be affordable relative to the residents’ income. In such areas affordable housing schemes may operate as a way to support rental housing for key workers (usually people working in lower paid, but key civic jobs such as police, health and education workers), rather than delivering housing that is affordable to very low and low-income households.

As Australian governments turn their attention to policy settings aimed at increasing supply of affordable housing, and while individual jurisdictions’ definitions vary, it’s essential that what we mean by ‘affordable housing’ is clearly defined in each program and for each project prior to funding.

Use of the term should aim to be broadly consistent; more importantly, each project relating to ‘affordable housing’ needs to clearly articulate what form of affordable housing it is delivering and for whom.

It is not necessary (or perhaps even appropriate) for the HAFF Bill currently before Parliament to impose a definition of affordable housing that could risk restricting too narrowly the variety of projects funded, stifle innovation, or create obstacles through incompatibility with States’ existing definitions. Instead, it would be preferable (or could be operationally required as part of the assessment of applications) that all projects funded through the HAFF include clear definitions of what affordable housing is being provided, and to whom.

When ‘affordable housing’ projects operate without a stated definition, there may be ambiguity about whether they are funding new social housing; new ‘for purchase’ housing; or implementing strategies to encourage the private market to supply new housing (whether for rent or for sale). It means there isn’t clarity around whether that project is targeted at very low-, low- or moderate- income households, or key workers. A lack of definition can also mean evaluations of ‘affordable housing’ projects are potentially inconsistent and unreliable.

How many households need affordable rental housing?

In determining current need for affordable rental housing, AHURI research has focused on households experiencing housing affordability stress. AHURI research identified that 80 per cent of very low-income households (i.e. households in the bottom 20%, or first quintile (Q1), of Australia’s income distribution) that were renting in the private market (in 2016) were paying unaffordable rents (i.e. more than 30% of income so that they were in housing affordability stress).

In addition, 36 per cent of low income tenant households (i.e. Q2 households with incomes between 20% and 40% of Australia’s income distribution) were also paying unaffordable rents. All up, the total number of Q1 households (305,000 households) and Q2 households (172,000 households) in housing affordability stress—just under 480,000 households—is greater than the number of all households in Tasmania, the ACT, and the Northern Territory combined.

The Federal Government’s Housing Australia Future Fund will fund 10,000 new affordable housing dwellings, and the new National Housing Accord will provide funding to deliver an extra 10,000 affordable dwellings. The Accord will require the States and Territories to support building up to an additional 10,000 affordable homes, bringing the Federal Government’s current commitment to 30,000 affordable homes by 2029.

Currently, there is no data available on the number of affordable rental dwellings in Australia, and therefore no way of knowing the size of the gap between the number of households that need affordable rental housing and the required increase in the number of affordable rental dwellings.

What is an affordable rent?

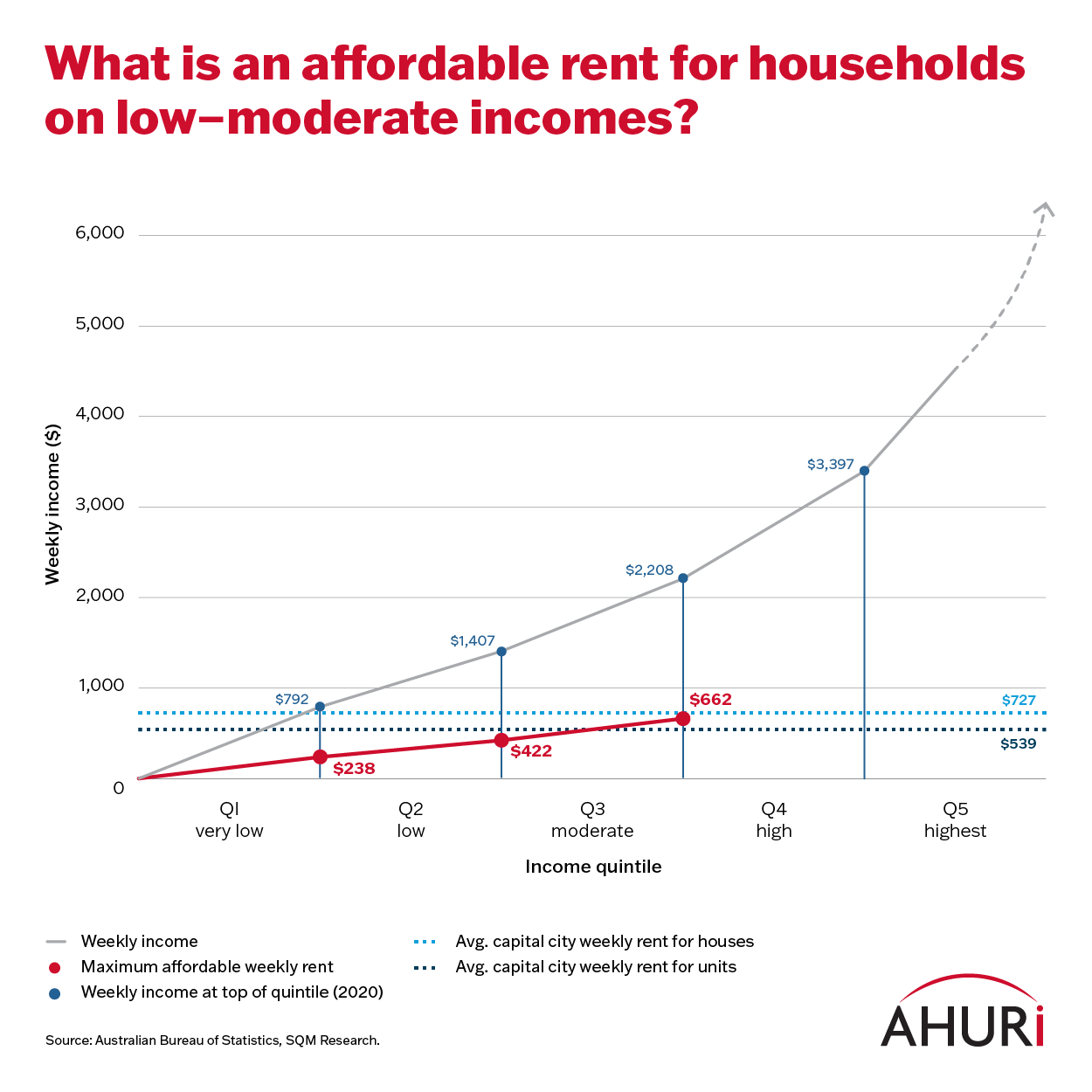

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has identified the maximum weekly income for households at the top of the Q1 and Q2 income levels. At the benchmark of rent being no more than 30 per cent of a household’s income, we see that the maximum rent a Q2 household could pay to avoid being in housing affordability stress is $422 per week (in $2020). In February 2023, the average rents across Australia for houses was $632 per week and $482 for units, with average rents for houses in the capital cities being even greater at $727 per week and $539 for units.

Typically, housing affordability stress has been the experience of Q1 and Q2 households but the high rents being asked, particularly in Australia’s capital cities, suggests that a number of Q3 households (i.e. those with ‘moderate’ incomes, between 40% and 60% of income distribution) will potentially also be experiencing a lack of affordable rental housing.

Quintile income: ABS Household Income and Wealth, Australia 2019–20. Household income and income distribution Table 1.2

Where should Australia focus to address our deficit of social and affordable housing?

In addition to the Housing Australia Future Fund and the National Housing Accord building commitments, the Federal Government is creating a National Housing and Homelessness Plan in order to encourage provision of the right types of housing in the right places. It is essential for this plan to prioritise delivering rental housing that is affordable to very low and low income households in areas that are close to employment and other amenities (including education and health facilities).

Government policies and subsidies to promote affordable housing in the private rental market should encourage landlords to deliver properties that are properly maintained and offer good security of tenure. Affordable rental housing policy should also support the expansion and sustainability of the not-for-profit community housing sector, including emphasis on both social housing tenants and tenants with slightly larger incomes (including Q2 and some Q3 households).

The Housing Australia Future Fund runs until 2030, however, given the size of the gap, it is clear we will need a longer term sustained effort. Dr Michael Fotheringham, Managing Director of AHURI, recently said,

“While there is now an urgent need for more affordable housing, we also face workforce and supply constraints which prevent us from simply building all of the needed housing immediately. We need long term ambitious targets and a sustained effort over decades.

We also need to look to other innovative and alternative policy responses to address our housing crisis, beyond new builds. Alternative programs such as NRAS, head leasing and rental brokerage programs can help generate affordable supply from existing stock.”

Australian governments now and into the future will need to work hard to address the failures of housing policy and underinvestment in past decades. They will need to ensure that stocks of social and affordable housing are not only increased to resolve our current crisis, but that appropriate stocks are then sustained in perpetuity for a more inclusive housing system for the generations to come.