Analysis of current and previous Australian urban policy frameworks identified a number of themes relating to the structure of Australian cities and desired social outcomes. This Brief investigates urban policies that have used place-based approaches with liveability, community wellbeing and healthy places as stated objectives, and reinforce the role of active community engagement.

Urban policies do not explicitly define what constitutes a ‘city’; instead, metropolitan planning strategies and infrastructure reports refer to place-based approaches at varying spatial scales including inner cities, the greater metropolitan areas of Australia’s capital cities, regions (such as South-East Queensland) and areas contained within these. The notion of place is strongly tied to concentrating economic activities and planning for the needs of residents within cities.

Place-based approaches

Metropolitan planning strategies operate at varying scales and scopes. Some plans focus on the overarching sense of the future needs of the city, whereas others work at very small spatial units.

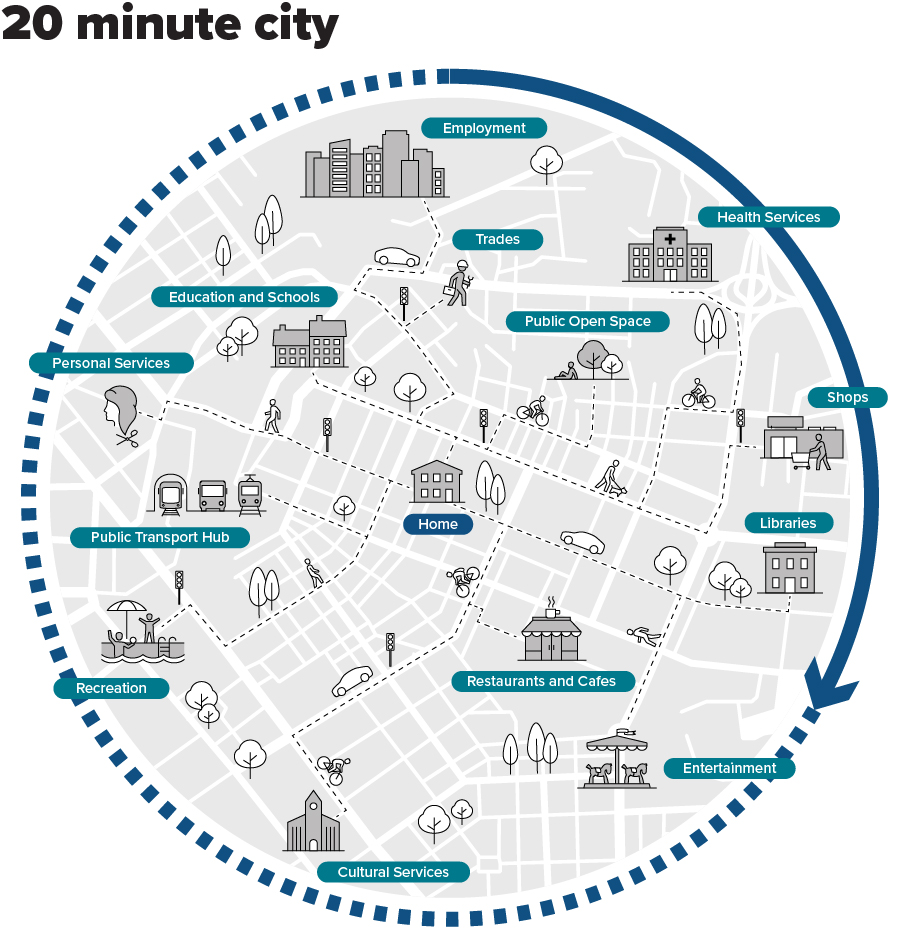

The concept of a 20 or 30 minute neighbourhood is an example of a place-based approach in which an urban policy engages spatially. A key objective of the Greater Sydney Region Plan: A Metropolis of Three Cities is to create a 30 minute city, in which most residents can travel to a metropolitan centre to access employment and services within 30 minutes of leaving home.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of place and raised the question around the structure of Australian cities and the role of the CBD in providing employment. For example, the number of pedestrians recorded by sensors in the City of Melbourne showed a large drop in the number of people walking in the city: from 550.85 people per hour (average for all sensors in the city of Melbourne) in Feb 2020—just before the COVID restrictions were introduced in mid-March—to a low of 74.93 in August 2020. In February 2022 the sensors recorded an average of 286.8 pedestrians per hour, around half (52%) of the number of pedestrians recorded in the city two years previously.

This suggests that people haven’t been coming back to the city in as large numbers as CBD-based retail businesses might want. While a proportion of that drop will be due to the disappearance of international students (who may or may not return in significant numbers), it does suggest people are changing the way they connect with CBD space, with research estimating that commuting activity will ‘decline by an average of 25-30% as both employers and employees see value in a work-from-home plan’.

AHURI research evaluated urban renewal programs in Australia on a neighbourhood scale, finding that these place-based interventions have the potential to provide greater social equity for disadvantaged communities and help allocate resources more efficiently. By facilitating walkable, lively and healthy neighbourhoods, planning strategies aim to connect local communities more closely and enhance social cohesion. Yet not all planning strategies clearly articulate place-based concepts and the way they are to be implemented. Rather, spatial outcomes are pitched at a conceptual level, with operational details left to local government authorities.

Urban policies propose investments in certain urban areas by identifying priority places for investment and through collaborative processes develop location specific strategies. Focusing on selected urban areas is seen as fundamental to achieving better urban design and place-making outcomes. For example, Infrastructure Victoria refers to several employment centres throughout metropolitan Melbourne to facilitate urban consolidation and bring people closer to their employment.

Liveability

Liveable communities are ‘safe, socially cohesive and inclusive, and environmentally sustainable. They have affordable housing that is linked to employment; education; shops and services; public open space; and social, cultural and recreational opportunities’. Liveability is shaped by the built environment. Providing green spaces and opportunities for active transport or social interaction are some examples of how ‘liveability’ might be delivered, yet how these outcomes can be achieved is rarely elaborated in planning strategies.

There is a heightened awareness of the importance of active transport options, and green spaces in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. AHURI research found that the use of mixed tenure, mixed use and mixed dwelling types may all contribute significantly to attempts to improve liveability, as well as de-stigmatise and rebalance the social profile of disadvantaged areas.

Victoria's 30-Year Infrastructure Strategy highlights the impacts of population growth and the role of infrastructure to support growing cities. The report refers to urban consolidation as the mechanism to ensure the liveability of Australia’s cities isn’t impacted. Within urban consolidation, infrastructure can play a key role in connecting people to jobs and supporting a healthy, educated workforce.

AHURI research found that the use of mixed tenure, mixed use and mixed dwelling types may all contribute significantly to attempts to improve liveability, as well as de-stigmatise and rebalance the social profile of disadvantaged areas.

Health and community wellbeing

The wellbeing of communities and the development of liveable and healthy places are social outcomes sought through cities policies. For example, research mapping COVID cases onto Sydney shows a strong correlation with both population density and disadvantage.

The same mapping also shows that, in general, less well-off suburbs of Sydney are more likely to be further away from areas of open space (that is, areas larger than 1.5 hectares). The research believes that ‘not all green space is equal. … with larger space allow a greater range of activities and more distancing’, both things that COVID restrictions reinforced as important for community health.

The Western Australian strategy Perth and Peel@3.5million emphasises the need when planning new urban areas to encourage more active forms of transport to combat declining community health and increasing obesity. Furthermore, to enhance the health and wellbeing of the community, the strategy promotes the delivery of health infrastructure in proximity to residential developments and aims to optimise the use of existing facilities.

Community engagement

The process of community consultation is an important element of any city or regional specific plan. However, within metropolitan planning strategies there was little mention of how ongoing community engagement might be carried out as the strategies are delivered. AHURI research shows that engaging communities in early stages of projects and in policy development will lead to better outcomes, mitigating risks of community opposition.

Policy frameworks of Australian infrastructure agencies frequently highlight the importance of ongoing consultation with communities to identify infrastructure challenges and solutions. Infrastructure Australia emphasises the need for infrastructure projects to be well-coordinated, make use of new technology and support broader reforms have the potential to make communities more resilient and sustainable.