A recent AHURI Inquiry researched the key drivers of population growth and mobility in Australia; the effects of economic agglomeration on the productivity of cities; and urban governance frameworks that have been planning for, and responding to, economic and population growth.

Regional and smaller cities

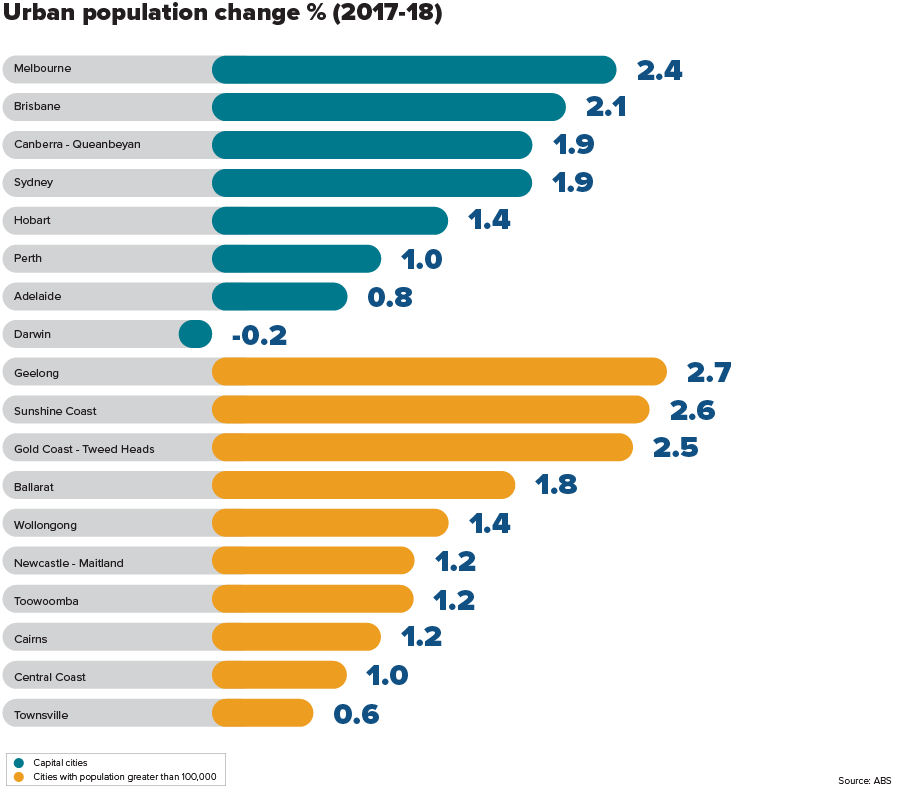

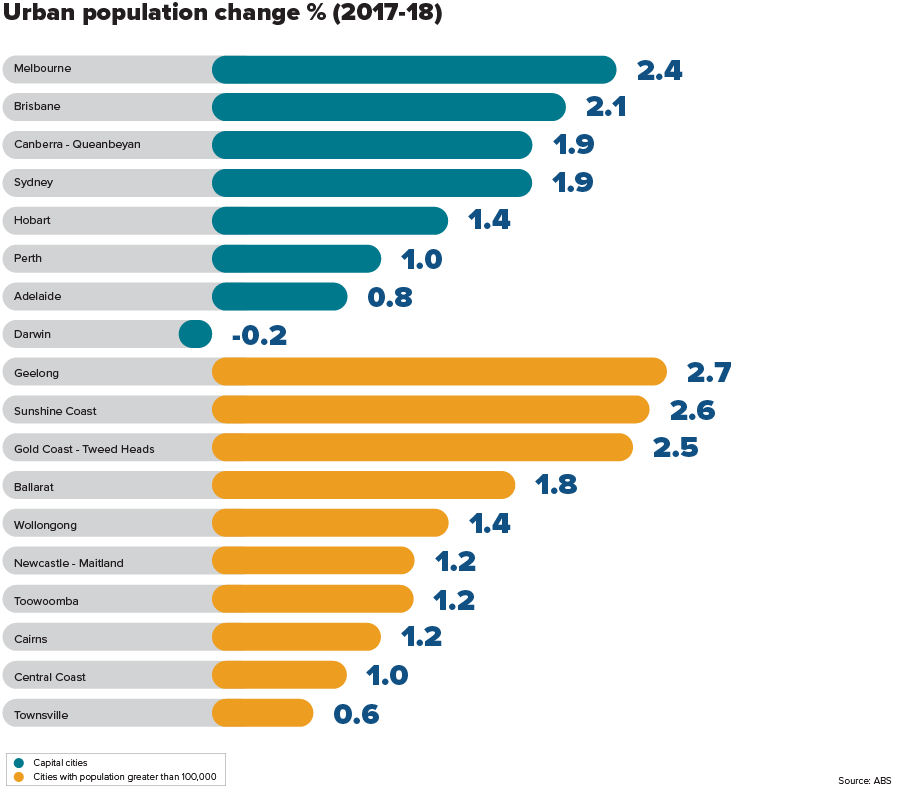

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many smaller cities, had lower population growth rates, in contrast to fast growing major capital cities. While the population of Melbourne increased by 2.4 per cent in 2018, several urban areas, including Darwin, Geraldton, and Rockhampton, experiencing a decline in population. For many regional cities, this trend shifted during the COVID-19 pandemic, with households moving out to regional areas. AHURI evidence has identified that the development of regional cities and their local economy is constrained by a lack of infrastructure and housing stock. For regional cities experiencing increased demand, including from inward migration, housing availability and affordability has been significantly reduced.

Infrastructure Australia had emphasised previously the role of governments to facilitate further population growth in regions to ensure on-going economic prosperity. Regional communities and economies should be supported by long-term planning and coordinating government and private sector investment. A recent Infrastructure Australia report identifies the availability, diversity and affordability of housing, broadband and mobile connectivity, water security, access to education and training, and lack of public transport as main infrastructure gaps.

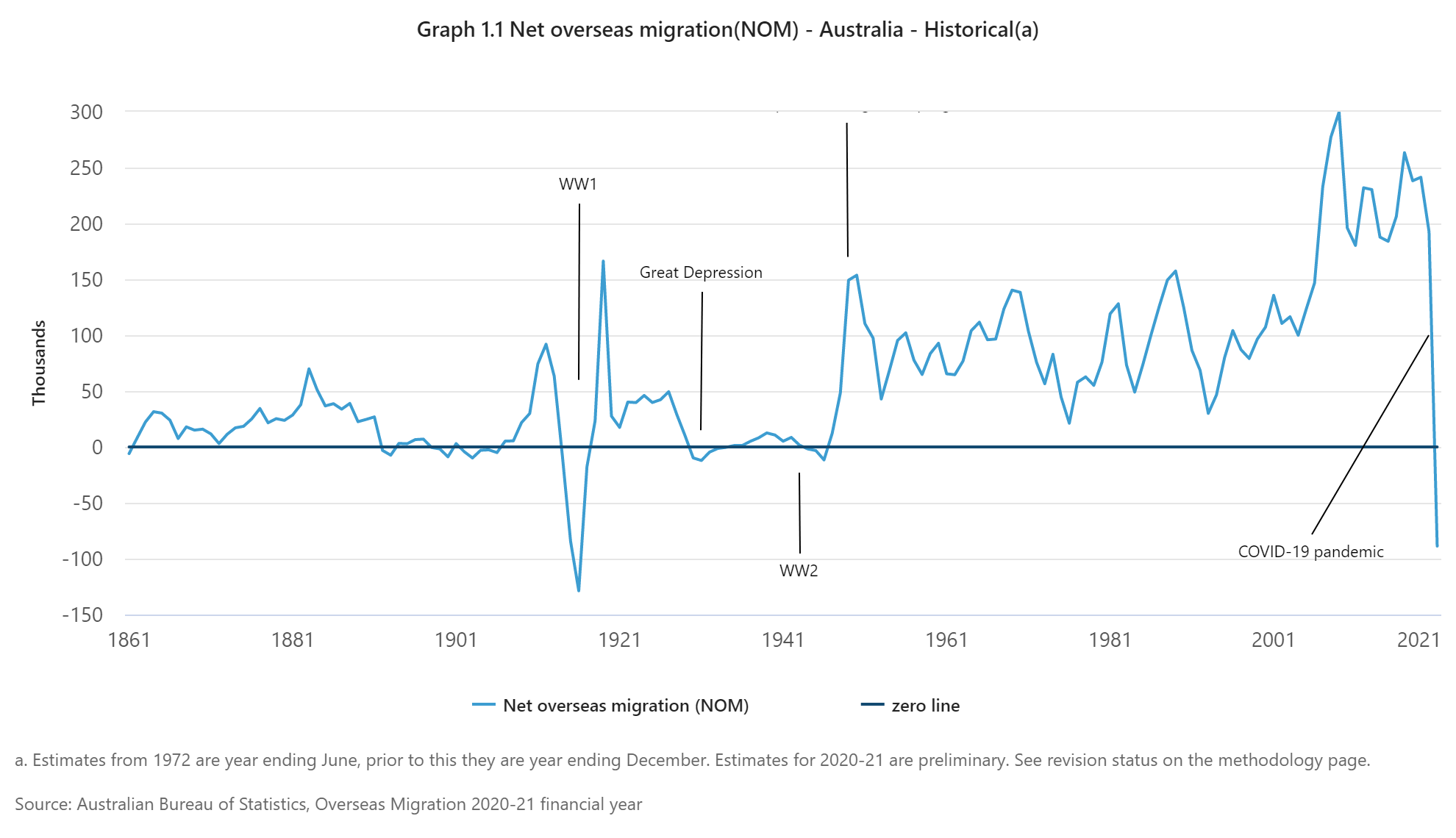

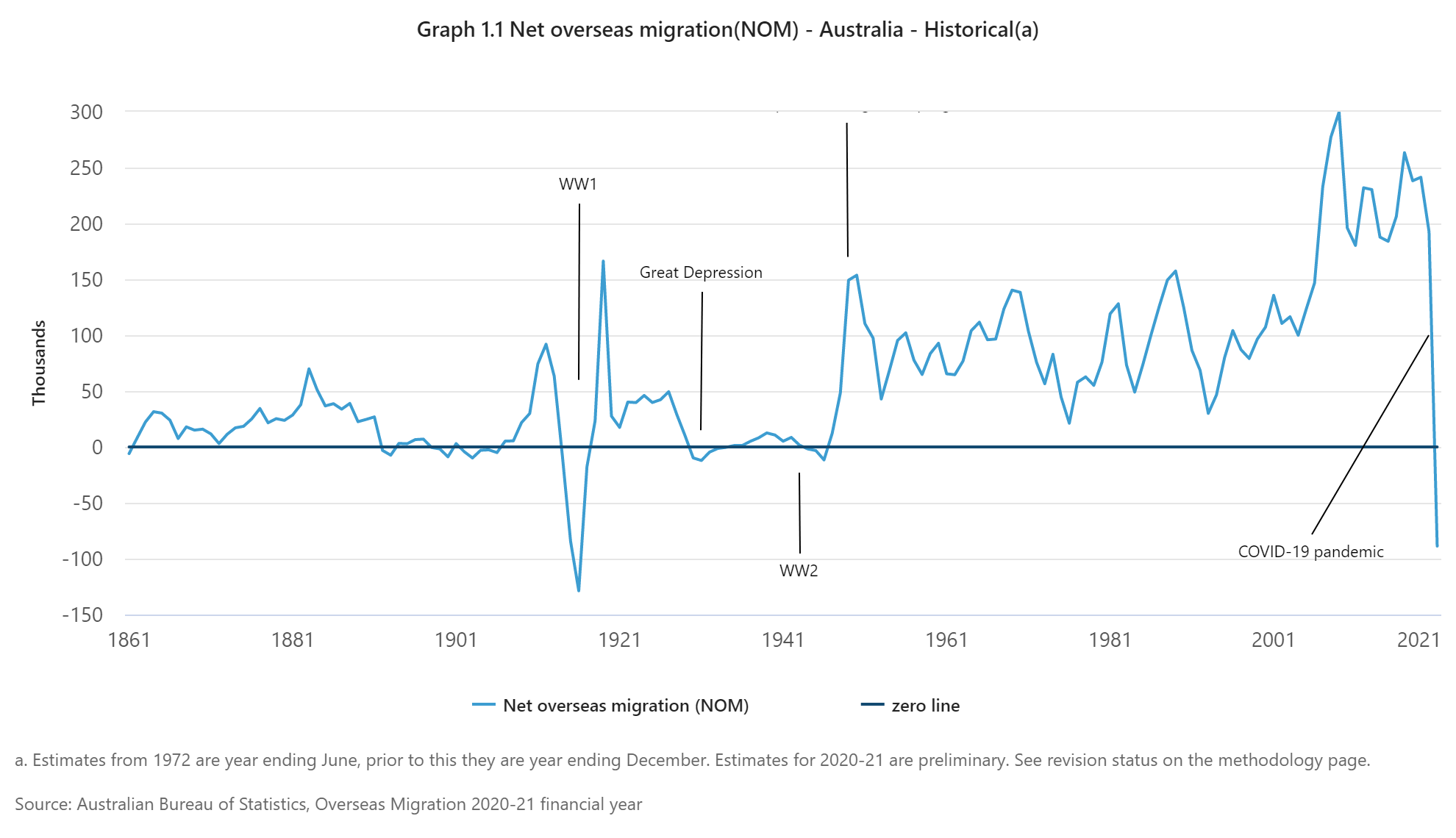

Migration

Prior to the pandemic, overseas migration constituted 62.5 per cent of Australia’s population growth. In 2018, net overseas migration resulted in a net increase to Australia's population of 237,200 people.

Major capital cities are the main place for migrants to settle. The Western Australian strategy Perth and Peel@3.5million, acknowledge the contribution of skilled migrants to cities’ prosperity and cultural diversity.

However, the settlement of migrants features less extensively in urban policies but is rather addressed in more general population policies. ‘Planning for Australia’s future population’ highlights the role of permanent migrants in addressing skill shortages in the economy and offsetting the effects of an ageing population. The strategy seeks to manage population growth by redirecting migrants to settle in smaller cities and regions instead of major cities.

Demographic change: ageing and household formation

The demographic characteristics of Australia’s population are changing, based on a shifting composition of households and an ageing population. AHURI research shows that demographic changes in Australia, such as an accelerated ageing of the population and substantial decline in household formation rates and average household size, is impacting home ownership outcomes, in particular for younger age cohorts.

Metropolitan planning strategies focusing on urban consolidation and higher density residential developments are taking changing demographics into account. In connection to the built environment, city policies could address the provision of adequate housing, social infrastructure and urban amenity in accordance with changing household compositions and needs.