The NSW State Government has announced that, as part of the upcoming 2022 State Budget, they will give first home buyers the choice of either paying stamp duty on their newly purchased property or paying an ongoing ‘annual property tax payment of $400 plus 0.3 per cent of the land value of the property. It will be available on homes valued at less than $1.5 million.’ The intention is to reduce upfront costs and thereby make housing more affordable for first home buyers.

This policy change follows a wealth of inquiries and reports including The Productivity Commission’s 5-year productivity review, ‘Shifting the dial’, that recommended state and territory Governments should ‘move from stamp duties on residential and commercial properties to a broad-based land tax on the unimproved value of land’

While the Productivity Commission report doesn’t directly include any modelling of the impact of such a reform, AHURI research has modelled the potential impacts on house prices and rents of replacing stamp duty with a broad-based land tax.

Understanding stamp duty

Nearly every time a property is sold or changes owners, stamp duty is paid by the buyer to the state or territory government. Stamp duty is determined by the value of land and the building although the amount charged varies in different states and territories, and it may be applied at different rates for owner-occupiers or investors.

Stamp duty affects affordability by making buying a home more expensive, especially for first home buyers. Stamp duty can also lead to the inefficient use of housing by constraining a household’s capacity to move to take advantage of new employment opportunities or to downsize to a more appropriately sized home.

What is a land tax?

Currently in all Australian jurisdictions (apart from the ACT) land taxes are applied to land used for commercial use and private rental housing but not for owner-occupied housing. Typically state and territory governments apply land tax once an investor has accumulated investment properties with a combined land-only value above a set threshold. As the value of landholdings increase, the land tax charged increases; for example in NSW in 2020 an investor with total assessable land holdings to $734,000 pays no land tax; between $734,000 and $4,488,000 they pay $100 plus 1.6 per cent of the land valued above $734,000; and pay $60,164 plus 2 per cent on the total of land valued above $4,488,000.

Land tax in its current form does discourage property funds and financial institutions from large-scale investing in the private rental housing market, a potentially significant factor contributing to the shortage of affordable rental housing.

By exempting owner-occupied residential housing from paying land tax, approximately 60 per cent of land by value (and 75% of residential land) currently is not included in the tax base.

Land tax in its current form does discourage property funds and financial institutions from large-scale investing in the private rental housing market, a potentially significant factor contributing to the shortage of affordable rental housing. As land tax is a cost to investors it is passed on to tenants in higher rent costs, which reduces housing affordability.

The impacts of eliminating stamp duty and having a universal land tax

Tax reviews, including the Productivity Commission’s 5-year productivity review, have proposed that stamp duty be removed and replaced by an annual universal land tax paid on all properties. This universal land tax differs from the current situation in that it would apply to all properties, residential and commercial, whether they are owned as an investment or by an owner-occupier.

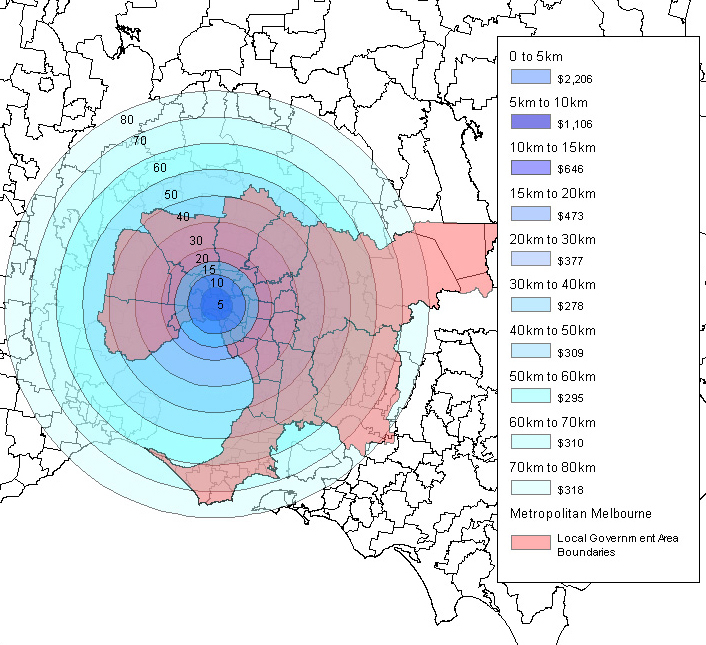

The Henry Tax Review in 2010 proposed that the land tax for each property be based on the number of square metres of land the property encompasses and its value. For example, the land for a more valuable property near the city centre or near a transport hub would be taxed at a higher rate than less valuable land in the outer suburbs or further away from desired amenities. This spatial distribution of land values is illustrated by Figure 1, which shows land values per square metre by distance from Melbourne CBD. Land value is highest in the CBD and declines systematically with distance outwards from the CBD.

Figure 1: Map of land values per square metre by distance from Melbourne CBD, 2006 (in 2006$)

Source: Wood, G., Ong, R., Cigdem, M. and Taylor, E. (2012) The spatial and distributional impacts of the Henry Review recommendations on stamp duty and land tax, AHURI Final Report No. 182

AHURI research modelling of a universally applied land tax shows it will be felt most intensely on land with higher value, which will attract a higher rate of land tax. The tax burden will be concentrated in the inner ring of business districts and suburbs where income per capita is correspondingly high. For example, almost half (46 per cent) of the land tax revenue would be raised from land plots within 10 kilometres of the CBD where land is most expensive, while only 4 per cent of land tax revenue would come from the urban fringe 30 to 50 kilometres out.