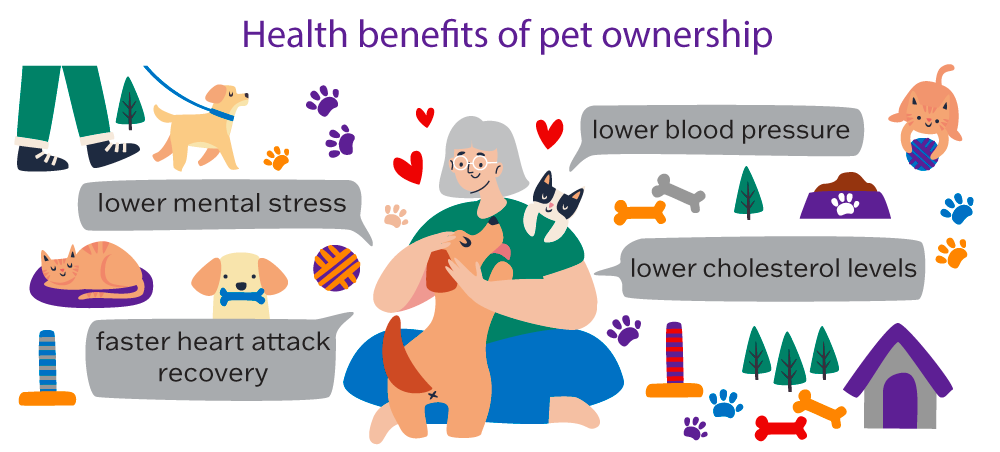

Around 6.9 million Australian households (69% of all households) had a pet in 2022, a rate greater than for both the US (66%) and the UK (57%). The physical and psychological benefits of having a pet have been recorded by a number of studies and include decreased blood pressure and cholesterol levels; increased physical activity; improving self-esteem; and reducing rates of depression and loneliness; with one study estimating Australian cat and dog owners saved approximately $3.86 billion in health expenditure over one year.

Even though there are demonstrable benefits in keeping a pet, the right to do so varies across Australia and depends on whether a household is renting or even where they are buying a home. For people buying into a strata title development (such as an apartment building) the body corporate laws that dictate how the common property areas are able to be used may also restrict households (including owners) from having a pet or a specific type and breed of pet. Owners may have the right to apply to the body corporate in writing to get permission to have a particular pet.

How pet friendly is the rental market?

For households renting in the private rental market the restrictions on pet ownership can be even greater with landlords often having the right to ban pets from their properties. This can restrict pet owning households from being able to rent properties in locations that provide good access to employment and educational opportunities, as well as restricting households leaving home ownership, launching from the family home or seeking to move out of social housing. Indeed an estimated 15–25 per cent of cases where people have to give up their pets are related to pet restrictions on moving to a new rental property.

In reality, evidence of pets causing property damage is limited, and damage is no more likely than for households without pets.

For many landlords there are perceptions that pets cause problems during tenancies, such as increased property damage or being a nuisance to neighbours through barking or aggressive behaviour. As a result, some landlords have asked for pet bonds to cover potential damages caused. However, vulnerable households who already bear the existing costs of rental housing transitions and risk of homelessness may not be able to afford any additional upfront housing costs. In reality, evidence of pets causing property damage is limited, and damage is no more likely than for households without pets.

Allowing pets in housing can benefit landlords, as there is some evidence that pet-friendly rentals have shorter vacancy periods and need less marketing, while tenants with pets stay longer and may pay higher rents. Openly providing pet-friendly housing also directly addresses issues with illegal pet keeping, where landlords and owners’ corporations are less able to regulate or monitor pets.