What this research is about

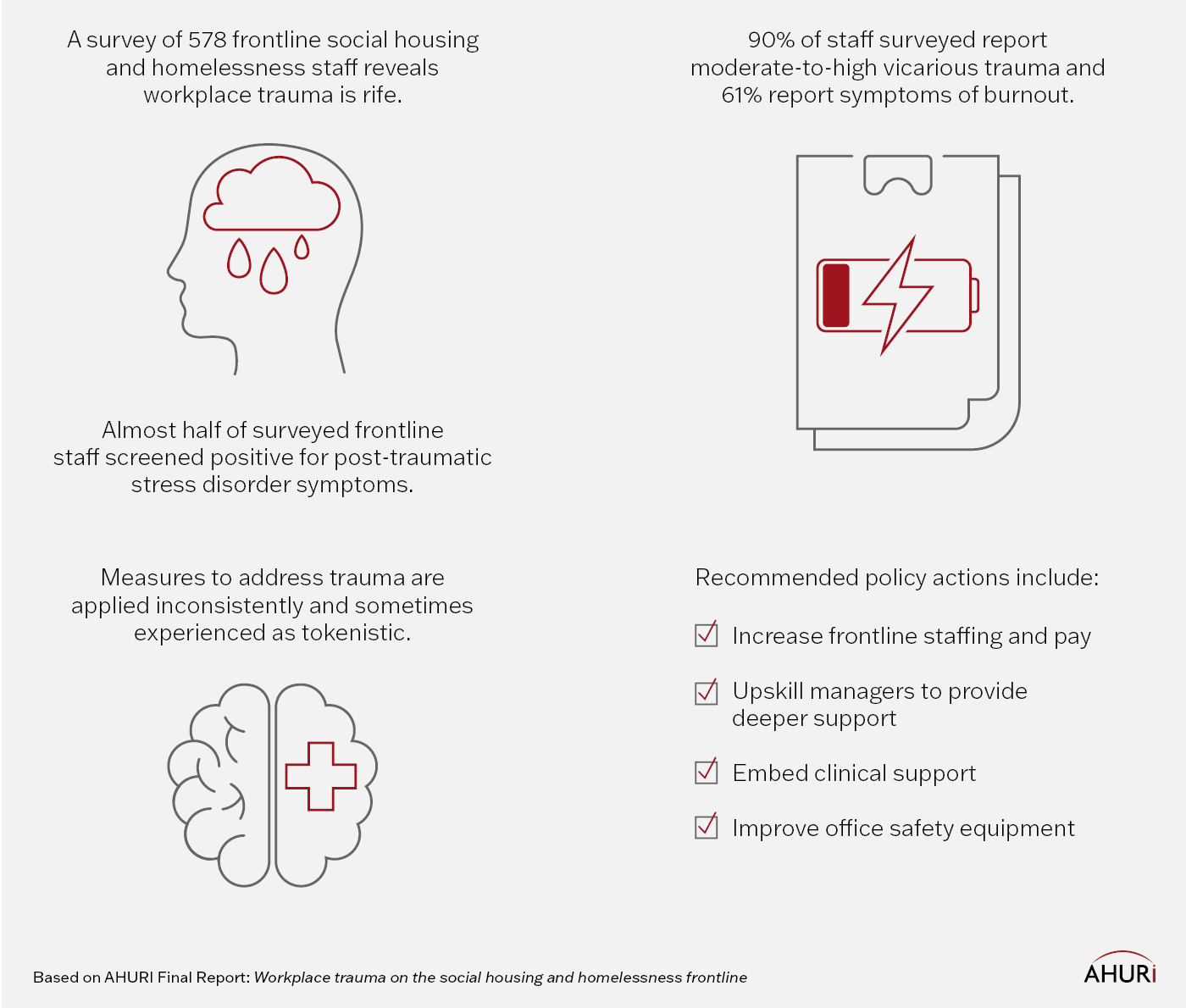

This research explores workplace trauma in Australia’s social housing and homelessness services – including its extent, causes and impacts. It examines current practices to address this trauma, options to mitigate it, and guiding principles for response.

Why this research is important

People working in the housing and homelessness sector are exposed to significant trauma due to their role as service providers of last resort for individuals with complex needs. A national survey of frontline staff reveals almost universal exposure to workplace aggression and tenant and client distress.

There is a need to understand how to minimise workplace trauma and create safer environments for frontline staff.

-

At a glance

-

Key findings

Trauma exposure an almost universal experience

Exposure to workplace trauma is frequent, cumulative, and embedded in frontline housing and homelessness work.

A national survey of 578 frontline staff in these sectors found high exposure to:

- Challenging behaviour: 98% of surveyed staff observed clients/tenants under the influence of alcohol or drugs and 91% had supported clients/tenants with experiences of family violence.

- Death, suicide and self-harm: 95% had spoken with clients/tenants about suicidal ideation, 88% had clients/tenants who had engaged in self-harm, and 78% had worked with a client/tenant who had died.

- Threats and abuse: 96% of surveyed staff experienced trauma due to verbal aggression, 85% due to threats against them or their families, 59% due to physical assault and 28% due to sexual assault from clients/tenants. Sixty per cent reported experiencing the presence of a weapon at work.

Impact on individuals

Workplace trauma can impact motivation, productivity and the ability to connect empathically with clients and tenants.

Among survey participants, 90% reported moderate-to-high vicarious trauma (trauma resulting from exposure to others’ traumatic experiences), 61% reported symptoms of burnout and 43% reported post-traumatic stress symptoms that warranted further assessment.

Many described impacts suggestive of compassion fatigue and moral injury, and significant impacts on their day-to-day lives including their lives outside of work.

Impact on organisations

Workplace trauma can lead to increased staff turnover, illness, and recruitment and retention difficulties. These can affect the quality and sustainability of frontline housing and homelessness services.

Context contributes to trauma

Workplace trauma in housing and homelessness services can be exacerbated by operational contexts, such as high caseloads and lack of supervision. It can also be exacerbated by systemic factors, such as managing emergency situations arising from failures and limitations of other services.

Current measures are failing

Organisational efforts to manage trauma (including incident-reporting systems, training and employee assistance programs) were widely described by survey participants as inadequate in preventing widespread harm.

Stakeholders identified time pressures, under-resourced teams, and lack of trained supervisors as factors undermining the ability to implement effective strategies.

-

Policy actions

Improved work design

The research finds that increased staffing and smaller caseloads, with guardrails to prevent overwork, should be investigated as measures to reduce workplace trauma.

Mandating a two-worker model (where tenant visits and outreach work are always attended by at least two staff) is also recommended.

Dedicated time for paperwork and job/task rotation should be supported to facilitate downtime for workers.

Improved conditions

Improved pay, leave options, flexible working arrangements, skills training and upskilling of managers should be considered to help manage and reduce workforce trauma.

Amendments to residential tenancies legislation could also be considered, to remove barriers to moving tenants who pose significant risk.

Physical workplace changes

Dedicated office safety equipment could be improved to support worker security, including via security screens, duress alarms and CCTV.

Boosting support supply

Clinical supervision, reflective practice and psychological first aid could be embedded across frontline housing and homelessness services. An employee assistance program could be centrally funded by government and peer-support networks for frontline workers should be resourced.

Increasing social housing and crisis accommodation would also assist, as would increasing social worker support for tenants.

Increased accountability and collaboration

Resource allied services to enable them to respond to the needs of social housing tenants and people experiencing homelessness. This includes mental health, drug and alcohol, family violence, child protection and justice services. Improved information-sharing between agencies would also minimise retraumatising clients and tenants.

-

Research design

This research involved surveys of frontline staff in the housing and homelessness sectors and interviews with frontline staff and stakeholders in New South Wales, Tasmania and Victoria. It also involved workshops to investigate workplace trauma in these sectors.