With median house prices declining in Australia, there has been debate about potentially reforming negative gearing, and with a federal election looming in early 2019 this debate will likely grow.

Negative gearing reforms were modelled in AHURI’s Inquiry: Pathways to housing tax reform, which proposed changes that improve the efficiency, equity and sustainability of housing tax policy, and also presented viable political pathways to achieving these outcomes.

In 2011–12 negative gearing costs to the Australian Government reached a high of $7.9 billion, which led to calls for the tax benefit for investors to be removed or reduced. The latest data available from the Australian Tax Office statistics shows the costs negative gearing to government has eased to $3.6 billion in 2015–16—still a significant amount.

Finding a way to reduce negative gearing impacts that is fair to both investors and government budgets, while preventing a large number of investors leaving the rental housing market, is.. necessary.

Research shows that negative gearing benefits are heavily skewed towards investors who have more wealth. In 2013–14, negatively-geared rental investors made a loss of around $8,800 on average but reported an average tax assessable income of $91,000. In comparison positively geared investors made a profit of around $16,000 and reported an average tax assessable income of $78,500.

Finding a way to reduce negative gearing impacts that is fair to both investors and government budgets, while preventing a large number of investors leaving the rental housing market, is therefore necessary.

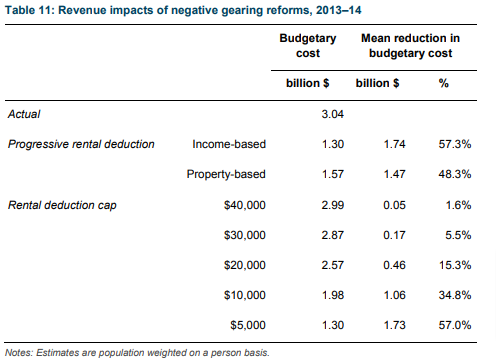

Table 1: Revenue impacts of capping negative gearing deductions, 2013–14

Notes: Estimates are population weighted on a person basis.

Source: AHURI Final Report 295 (calculated from 2013 ABS Survey of Income and Housing)

AHURI research identified that one option may be to cap the level of deductions an investor may claim. If a $40,000 cap is imposed, the average tax saving for a negative-geared rental investor is reduced by only $25. If a $5,000 cap is imposed, average negative-geared rental investors will pay extra tax of $921 each year (based on 2013–14 tax statistics).

If a $5,000 cap was implemented it would result in a $1.73 billion tax saving to the Australian Government.

Another option identified is the progressive rental deduction model whereby investors in the bottom half of wealth distributions continue to enjoy all negative gearing rental deductions—and therefore experience no reduction in tax savings, while those in the next quarter of wealth distribution (i.e. the 51st–75th percentiles) can only claim 50 per cent of their rental deductions, and those in the top quarter of wealth distribution (i.e. 76th–100th percentiles) can claim no rental deductions. For some high value investors this could equate to an average loss of $3,149 per year.

A progressive rental deduction based on investor income would result in a $1.74 billion saving to the Australian Government.

The research also modelled progressive rental deductions based on the value of properties owned by an investor. In this case rental investors in the bottom 50 per cent of the rental property value distribution can continue to claim all negative gearing rental deductions, those in the 51st–75th percentiles receive a lower 50 per cent rental deduction, while those in the 76th–100th percentiles can claim no rental deductions. Under this modelling the Australian Government would save $1.47 billion.

Both a rental deduction cap of $5,000 and progressive rental deduction based on income are progressive in nature as they reduce tax savings from negative gearing by greater margins as tax assessable income increases.