Social housing is completely overstretched. Re-imagining the system could support more people.

03 Jun 2025

With the cost of living crisis and rising rents across Australia there is growing recognition of the need for social housing to help even more people. Although governments provide subsidised homes to 423,000 vulnerable and low income households, the demand is outstripping supply.

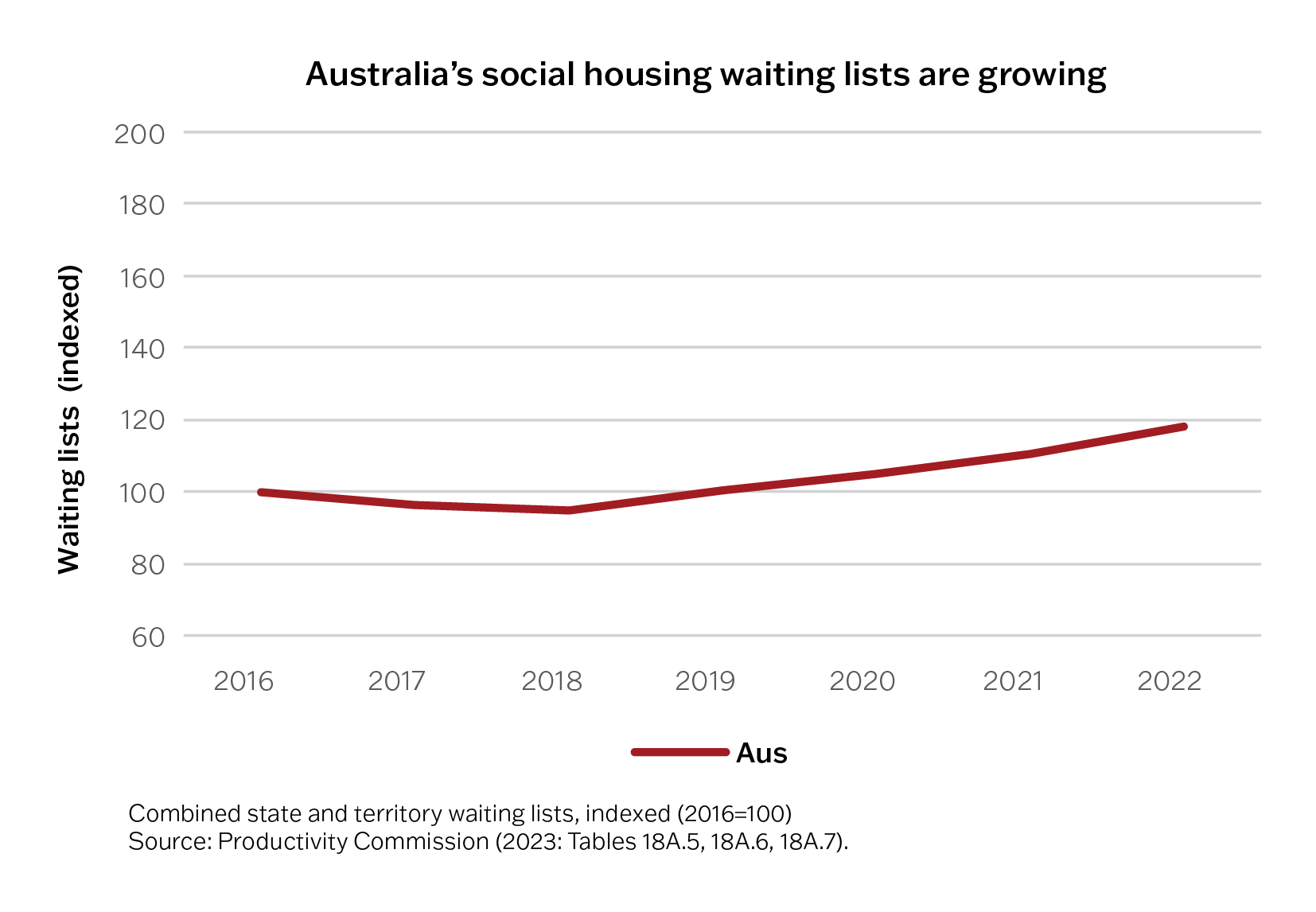

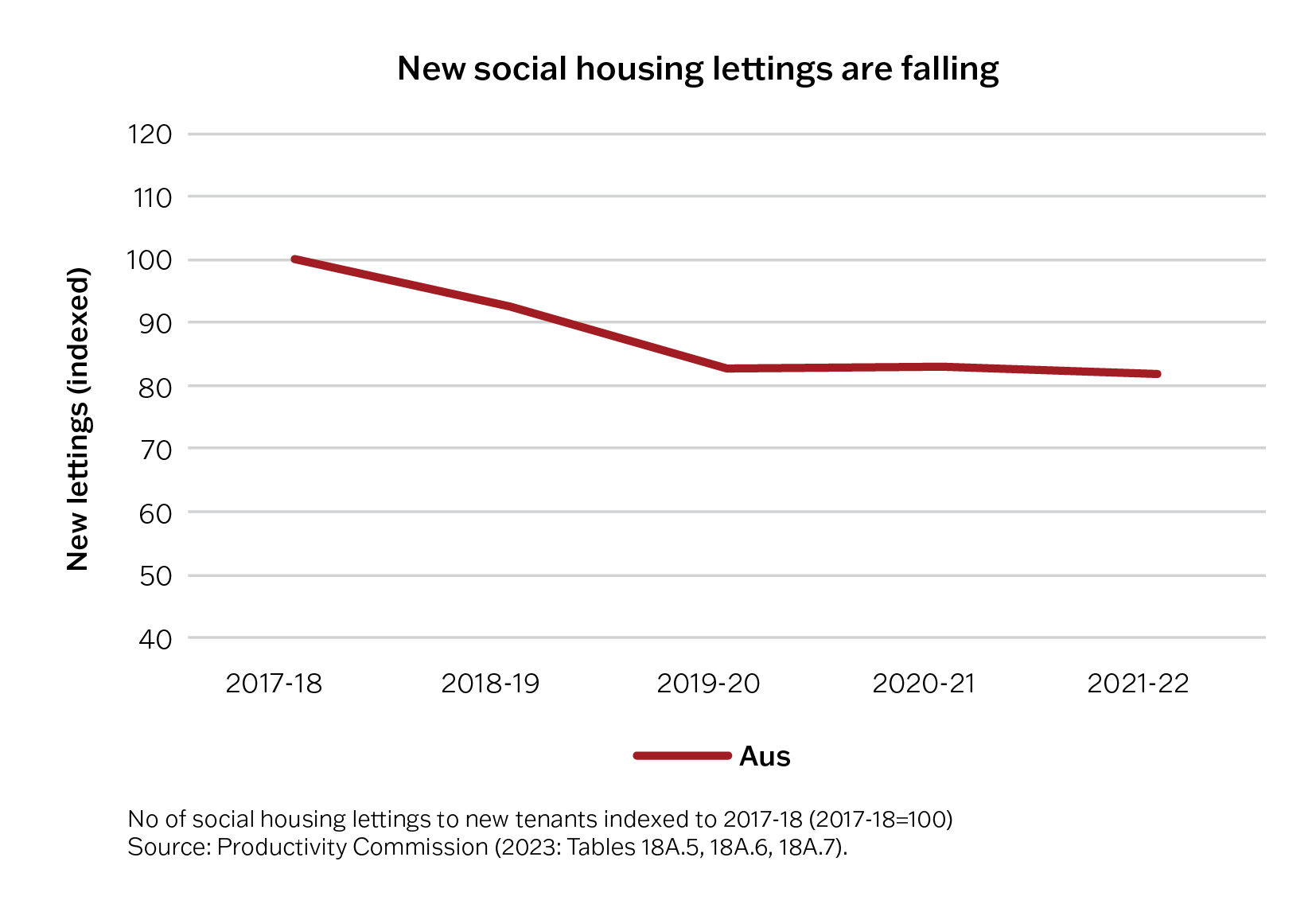

In the 6 years to 2022, Australia’s social housing wait-lists grew by more than 26,000 households, while the number of households able to get into social housing fell by 6,400 (see graphs over page). It’s a situation putting a huge strain on a growing number of households, many of whom are aged over 50 or live with disabilities.

In addition to highlighting the urgency for more social housing to be built, new AHURI research, ‘Inquiry into socially supported housing pathways’, suggests governments could go further to re-imagine the social housing system and transform social housing assistance.

Re-imagining housing pathways can help people even when no social housing is available

‘Housing assistance needs to be delivered differently,’ says lead author of the research, Dr Chris Martin from UNSW Sydney. ‘Australia’s social housing system needs to make stronger assurances of different kinds of housing assistance that reach beyond the constraints of unavailable social housing stock. It needs to do more for the people who are waiting, as well as for those already in social housing.’

A re-imagined social housing system would focus on households and their different needs and support options, instead of revolving around a rationed stock of social housing dwellings. It could encourage different housing assistance options such as rent subsidies for very-low income households living in the private rental sector, forms of temporary accommodation, bond assistance and first home buyer assistance.

Re-imagining Legislative reforms can improve effective housing assistance

Australia’s housing assistance system is delivered by state and territory housing authorities and community housing providers. The Commonwealth government also provides support such as Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Legislative changes could give greater clarity on eligibility and entitlements to social housing and rent assistance.

‘Our research suggests that housing policy makers need to look at the sector’s legal foundations, which are surprisingly slender,’ says Dr Martin. ‘While state and territory governments have statutory authorities that own and manage public housing, their laws say little about how they are to operate and support people. Important issues such as eligibility are left to policies that can be changed with little oversight, or not kept up with changes in housing costs and incomes. These laws also don’t refer to other forms of housing assistance that may be offered by social housing providers. This means the system makes legally weak assurances of assistance.’

‘Housing legislation should enshrine the right of individuals to reasonable and necessary housing assistance, and provide for a range of forms of housing assistance that are designed in participation with recipients to better meet their needs’ says Dr Martin.

Co-designing social housing assistance could lead to a better system

State and Territory housing authorities could use a co-design approach to refocus social housing policies and practices. This could mean designing policies and new forms of assistance with the participation of tenants, people with lived experience, frontline service delivery providers and housing and homelessness sector representatives.

Housing providers and applicants could also adopt co-design principles to develop targeted individual housing plans. Such plans can benefit priority applicants—as a focus for support work—as well as non-priority applicants. This may create possibilities for alternative forms of housing assistance for applicants on waitlists for social housing.

This research was undertaken by researchers from UNSW, RMIT University and Swinburne University of Technology.