Improving CRA could help older tenants in the private rental market

01 Dec 2022

Life course changes associated with older age such as widowhood, disability and frailty suggest a need for a range of rental housing options. These include a private rental sector (PRS) that can support older tenants living in the general community, as well as options such as communal self-contained living spaces that provide some level of companionship, practical support and assistance with daily living, through to facilities that combine health care, personal care and accommodation.

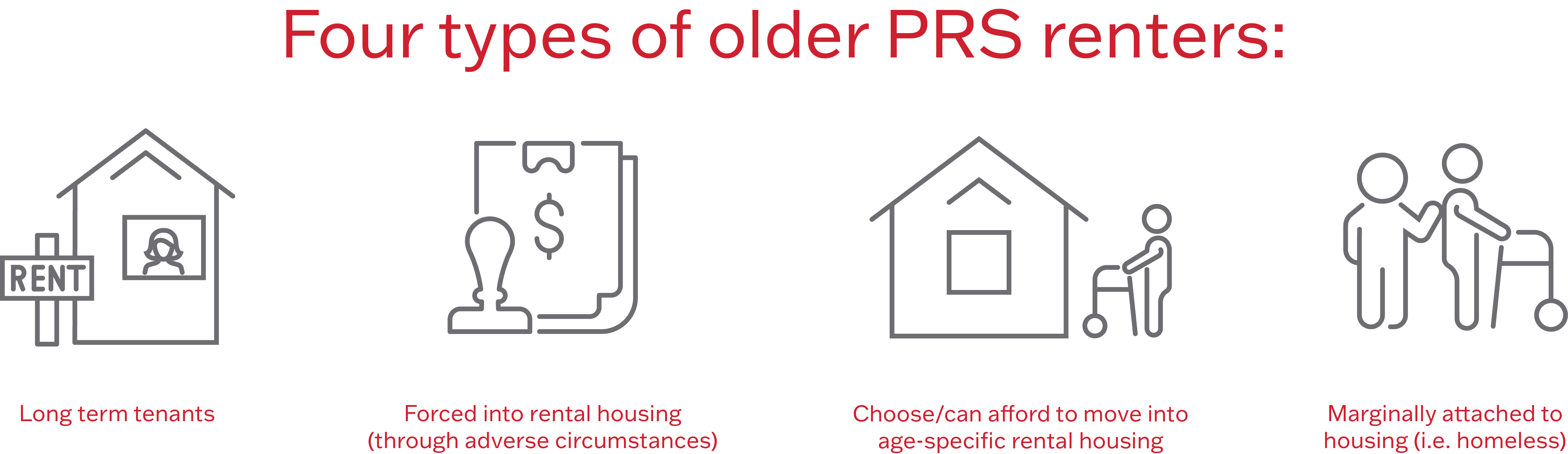

Housing policy options need to consider that there are four types of older PRS renters: some are long-term tenants; others are forced through adverse circumstances into rental housing (i.e. divorce, bereavement, financial circumstances); others choose / can afford to move into age-specific rental housing (e.g. resort style age housing); and some are marginally attached to housing (i.e. experiencing homelessness). Housing providers, including those in the PRS, must respond to this diversity of experience and preference.

Older renters – the key issues

Retired lower income households living in the PRS face rent increases and insecure tenure while being on low fixed incomes (i.e. the age pension). They also live in housing that may not be physically suitable for them and may require alterations to make the premises liveable (e.g. wider door openings to allow for wheelchairs, height adjustable kitchen benches etc.).

As tenants get older they are not be able to cope psychologically with stress and changes; may be suffering from physical disability and mental health concerns; may be frail and vulnerable; and can suffer from being isolated.

Finding housing solutions that are secure, affordable and appropriate to older renters is the key to keeping these tenants in their home and not being dependent on residential aged care.

Increasing Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) for older tenants

Currently CRA is paid to an eligible ‘income unit’, which may be a household made up of a couple or an individual.

In the case of a household made up of a couple who both receive the age pension, if one partner dies (or leaves the relationship) the amount of age pension the surviving householder receives is effectively halved. However the amount of CRA the householder can receive is unchanged (i.e. the ‘economic unit’ is unchanged), meaning the person staying in the property has to continue to pay the same amount of rent as previously while receiving the same amount of CRA as previously but only have income from one age pension. As a result, rental costs now take up a significantly greater proportion of that individual’s income.

CRA could be restructured along the same lines as Housing Benefit in the UK, where there is a separate income test so that when a person suffers an abrupt reduction in income, Housing Benefit automatically increases up to a maximum of 100 per cent of the rent.

There are concerns such a reform will lead to work disincentives; however, for older tenants who are beyond retirement age these disincentives are of less concern. A separate income test for the over-65s would raise fewer concerns of this kind.

Such changes would be better targeted because older CRA recipients do not have an earnings profile to pay rising rents. The income tests can also be made sensitive to household type, so that they offer proportionately more support to singles, who often face greater financial hardship as they cannot benefit from the economies of scale in consumption that couples can.