Why does Australia have a rental crisis, and what can be done about it?

16 Nov 2022

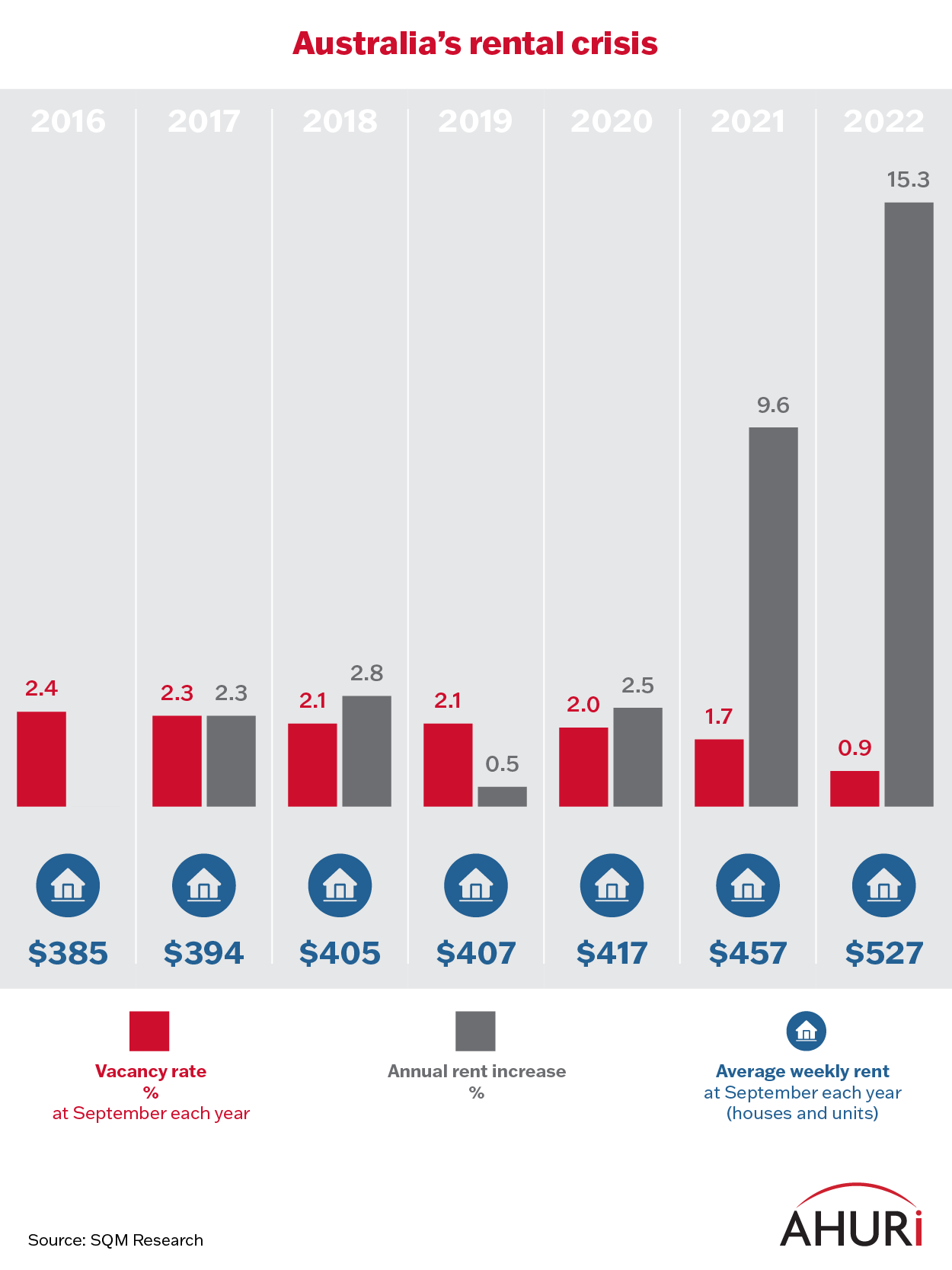

Australia is experiencing a period of very low rental vacancy rates and rising rent levels, which has led to what is widely recognised as a ‘rental crisis’. Indeed, the national rental vacancy rate (i.e. the percentage of untenanted rental properties against all rental properties) was at 0.9 per cent in September 2022, the lowest since April 2006 (when it was 0.8% for one month). This very low vacancy rate has been sustained for most of 2022, a situation not seen in the last 20 years.

Such pressure for rental housing pushes up rents, and as a result national combined rents (i.e. that is for houses and apartments) are the highest they have ever been: $542 per week (for November 2022).

Why do we have a rental crisis?

This crisis of unaffordable and unavailable rental housing is the consequence of a number of causes and will require a variety of solutions.

Not enough homes to keep up with population and household growth

At a basic level, Australia needs sufficient new housing to house the nearly one million new households formed between the 2016 and 2021 Census; an 11.9 per cent increase (or an average of 197,826 households per year). One reason for the increased number of new households is that there was a large 17.1 per cent rise in the number of single person households between 2016 and 2021 Censuses, in part caused by relationship breakdowns and share houses dissolving due to COVID lockdowns. By comparison, there was only a 7.1% increase in single person households between 2011 and 2016 Census.

The number of new residential dwellings did not keep up with the number of new households, increasing by only 10.6% per cent (around 198,000 new dwelling each year). This number includes unoccupied dwellings, such as second homes or holiday houses, which are not available for rent or purchase by newly formed households.

As the rate of household formation is greater than the increase in new dwellings, this leads to increased pressures on housing demand.

Table 1: Rental vacancy rate and rent increase, Australia 2016–2022

Table 2: Population and household numbers, Australia 2016–2022

| Australia | 2016 Census | 2021 Census | % change 2016-21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 23,401,881 | 25,422,789 | 8.6% |

| Households | 8,286,078 | 9,275,212 | 11.9% |

| Rented dwellings | 2,482,548 | 2,842,378 | 14.5% |

| All private dwellings | 9,325,958 | 10,318,993 | 10.6% |

To further compound the pressures of increasing household formation, there is a slowing of the numbers of new housing being built. There was a 2.7 per cent reduction in the number of new residences being built in Australia in June 2022 (compared to the previous quarter). The number of new dwellings being completed in the year to the end of June 2022 (174,931 dwellings) was 18.6 per cent less than in the year to the end of June 2019 (214,819 dwellings), before world-wide COVID restrictions applied. Supply chain problems and worker shortages are slowing down home building and leaving projects unfinished, adding to housing pressures.

Internal migration

While the national rental vacancy rate is bad, it does vary across cities and regions. In September 2022 Melbourne recorded a rate of 1.4 per cent, Sydney of 1.3 per cent, Canberra of 1 per cent, Darwin of 0.7 per cent, Brisbane of 0.7 per cent, Hobart of 0.5 per cent, Perth of 0.4 per cent and Adelaide of 0.3 per cent. Regional areas also fared very poorly, with examples of Cairns and Gold Coast (QLD) both recording 0.5%, while Far North Coast (QLD) has a vacancy rate of 1 per cent and Kangaroo Island (SA) recorded 0 per cent.

Between 2016 and 2021, regional Australia gained 184,000 people who moved from having previously lived in a capital city, more than double the number of 81,600 people revealed in the 2016 Census. This increase was predominately driven by people moving to regional and rural Queensland (+63,700), regional and rural Victoria(+62,900) and regional and rural NSW (+59,000). Such large internal migration numbers have a real impact upon local vacancy rates in regional and rural areas, particularly in Queensland.

International borders reopening

The lack of rental housing was temporarily alleviated during the COVID pandemic when international students and workers were restricted from living in Australia. At that time vacancy rates across Sydney reached 4 per cent in May 2020 (and 16.2% in the CBD) and 4.7 per cent in Melbourne. Numbers of overseas arrivals plummeted from a high of 2.26 million in January 2020 to a low of 10,000 in August 2020 but started to climb again from November 2021 (70,000 arrivals) to 1.07 million in September 2022. International students arrivals have grown from just 230 individuals in August 2021 to 40,650 in August 2022. While this is perhaps not a key reason for current housing affordability stress, it is a factor in that, as Australia’s borders are reopening and the demand for rental housing is increasing, the vacancy rates have dropped to dramatic lows.

The impact of short-term rental

The impact of rental housing being removed from long term rental to the short-term letting market (e.g. AirBnB) has also been a factor in worsening vacancy rates, but generally only in specific areas. AHURI research shows that ‘short-term letting platforms like Airbnb are probably not significantly worsening rental affordability across our major cities as a whole but are having an impact on the availability of rental properties in high-demand inner city areas with significant tourism appeal.’

For tenants in tourism-rich regional and coastal areas the impact of short-term letting is apparent. Prior to COVID, AHURI research focussed on Tasmania showed a steady increase in properties being available in the short-term letting market between 2016 and March 2020. Despite a large fall in short-term letting activity after March, the research shows that people began using the short-term letting market again after June 2020.

What can be done to improve Australia’s rental crisis?

At its simplest, to reduce the rental crisis Australia needs to build more well-located rental dwellings that are affordable to people on low incomes. Strategies to make this happen can include targeting Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) more effectively; increasing CRA to better align with rents in local areas; and improving connectivity between outer suburban and satellite city housing markets and job-rich areas.

Build the right kinds of homes in the right places

While keeping the price of housing down is essential, it’s also vital that affordable housing is built in the right areas. Recent 2021 AHURI research reveals that although low-income households (i.e. with household incomes between 21 and 40 per cent of Australia’s income distribution) are a critical part of the workforce, they are increasingly unable to find affordable rental housing near the employment centres of Australia’s major urban areas. Across Australia, there is a shortage of 173,000 affordable dwellings in the private rental sector available for these households, and 71 per cent pay an unaffordable rent that is greater than 30 per cent of household income.

The result is that working low income households are ‘either enduring affordability stress, commuting burdens, or both in order to access employment opportunities.’ To reduce the mismatch between employment rich areas and affordable housing, AHURI research identified three primary policy options: ‘increasing affordable rental housing near key employment areas; improving accessibility and connectivity to outer suburban and satellite city housing markets via strategic investment in transport and communications infrastructure; and ‘concentrated decentralisation’ —fostering new employment clusters through strategic place-based funding interventions and digital innovation.’

To help ensure the right kinds of dwellings are built in the right places, AHURI is currently conducting a research Inquiry,’ ‘Inquiry into projecting Australia’s urban and regional futures,’ to gain new insights into population dynamics and growth, including the drivers of regional mobility, across Australia’s cities and regions. The Inquiry’s findings will inform and guide future settlement and infrastructure planning at national, state and local levels.

Target rental assistance more effectively

Since its introduction in 1958 CRA was ‘indexed to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), so where rents have increased more than CPI, the real value of CRA has not kept up’. In fact currently over one-third of low-income CRA recipients are still in housing affordability stress after CRA is deducted from their rents.

To overcome the inability of CRA to fully support low income tenants’ housing costs AHURI has modelled reforms to CRA. Targeting the eligibility rules to those who fully need it could cut the numbers of CRA recipients who are in housing stress by 44 per cent. At the same time, it would generate an annual cost saving of $1.2 billion. However, as a Commonwealth funded welfare assistance program, CRA is restricted by constitutional limitations in that ‘the Australian Government is empowered to make certain social security payments only, which do not include rent or other housing payments in their own right.’ A work around could involve the Commonwealth Government making grants to the states and territories ‘to pay Rent Assistance to eligible persons’.

Increase supply of land and homes in places where they are needed

Of course, not all low income, renting households live (or want to live) in a city or major urban areas. However, the availability of rental housing is often very restricted in regional and rural areas. Although land might be a lot cheaper than in major cities there can be constraints: land zoned for agriculture is not able to be built on; and there are higher costs in building in the regions due to shortages of specialised labour, extra costs to bring in building materials, requirements to build to expensive standards in bushfire prone areas, difficulty obtaining bank loans in economically restricted areas, and higher costs of housing insurance in areas at risk of fire and flood.

As a result of such economic risks, private rental sector investors are less enthusiastic about committing to regional and rural area housing, particularly as regional households generally have lower incomes than metropolitan households (and can’t afford overly high rents), and capital growth is usually greater in metropolitan areas (although people moving to regions to escape COVID did push up regional dwelling prices by 5 per cent per annum by July 2020, which overtook the growth rate in cities at that time).

Increases to CRA for tenants in regional and rural areas may see tenants able to pay rents that could stimulate an increase in rental housing supply, particularly an increase in affordable social housing provided by community housing providers.

The newly announced national Housing Accord, which aims to encourage the building of one million new well-located homes over five years from 2024, recognises that the Commonwealth Government has a ‘a key role in enabling and kick-starting investment.’ Although most of the new housing will be supplied by the private market, the Accord is intended to expedite development such as by providing ‘financing options through the Housing Australia Future Fund to facilitate institutional investment in social and affordable housing’.