Between 1.5 and 2 million Australian renters at-risk of homelessness: report

New AHURI research finds that arge numbers of renting households are perhaps only one life shock away from homelessness.

26 Nov 2021

Large numbers of renting households, estimated to include somewhere between 1.5 and 2 million Australians aged 15 and above, are perhaps only one life shock away from homelessness, whether that’s a relationship breakup, getting a serious illness or losing work due to economic circumstances such as what happened during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, new AHURI research has revealed.

The research, ‘Estimating the population at-risk of homelessness in small areas’, undertaken for AHURI by researchers from Swinburne University of Technology, University of Tasmania and Launch Housing, estimates rates of people at risk of homelessness for small areas, including Statistical Area level 2 (SA2) data. SA2s typically have a population ranging from 3,000 to 25,000 people and can be thought of as a suburb or small group of related suburbs.

‘A person is considered at-risk of homelessness if they live in rental housing and are experiencing at least two of the following: low-income; vulnerability to discrimination; low social resources and supports; needing support to access or maintain a living situation (due to chronic ill health, disability, mental illness or problematic use of alcohol and other drugs); and are in a tight housing market,’ says lead researcher, Post-doctoral research fellow Deborah Batterham from Swinburne University and Launch Housing.

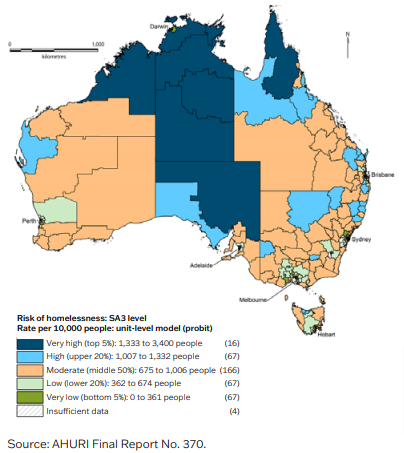

According to the research, the greatest numbers of people at-risk of homelessness are in NSW, Victoria and Queensland, the three most populous states. However, the highest rates of risk per 10,000 persons are in the Northern Territory, followed by Queensland and South Australia. The lowest rates of risk are in the ACT followed by Victoria. The suburbs with the highest rates of Australians at risk of homelessness are in remote areas and in small pockets of capital cities, while the greatest number of people at-risk of homelessness are living in greater capital cities on the eastern coast of Australia.

Figure 1: Risk of homelessness (rate per 10,000 people), unit-level SA3 estimates

The research shows distribution of those at-risk of homelessness varies greatly for different suburb-sized areas across Australia, from a low rate of homelessness risk of 87.3 per 10,000 people in Gelorup-Stratham (0.87%), a suburb of Bunbury in Western Australia, to 5,040 per 10,000 in Aurukun, in the remote northern most parts of Queensland (50.4%).

‘We can’t reduce homelessness by solely responding to people when they present to homelessness services, instead we have to turn off the tap up stream, as it were, by delivering preventative interventions that are tailored for specific areas,’ says Dr Batterham. ‘Understanding the population at-risk of homelessness is critical in designing and implementing such interventions.

While some of the policy leavers for addressing risk of homelessness are Commonwealth responsibilities, such as levels of welfare payments and Commonwealth Rent Assistance, much of the planning and delivery of social and affordable housing and health and disability services for example, is done at state and local government levels.

The report finds Australians at risk of homelessness are more likely to be female; Indigenous; living in a lone person or lone parent household; identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual; and report fair or poor health. Those at-risk have lower levels of educational attainment, are more likely to report difficulty paying bills and rent on time and are more likely to experience a range of indicators of material deprivation such as skipping meals and being unable to heat their home.

The use of more localised SA2 data in the research, provides several lessons for policy makers, as, for any area or region, there is a need to make a distinction between the rate of homelessness risk and the magnitude or number of people at-risk.

‘Some areas with an estimated high rate of homelessness risk have comparatively small populations, meaning that the number of people at-risk, in comparative terms, is small. Nevertheless, because of the higher rate, more people will be living alongside other people who are at-risk,’ says Dr Batterham.

‘Conversely, many capital city areas have low or moderate rates of homelessness risk. However, due to the much larger number of people in these areas, this translates into a much larger number of people at-risk and potentially a more substantial commitment of resources.’