Housing assistance reforms needed to support the wellbeing of people in precarious housing

The gap in wellbeing between the precariously housed and non-precariously housed widened over the period 2002–2018 according to latest AHURI research.

25 Feb 2022

New AHURI research has found a widening gap in the wellbeing of people living in precarious housing versus those who are non-precariously housed.

The study, led by researchers from Curtin University, examined different population subgroups between the period 2002 to 2018, finding the wellbeing of singles, households with no children, low-income households, private renters and major city residents worsens when they are precariously housed.

‘Wellbeing is an internationally recognised yardstick of societal progress and policy impact and refers to the ability of people to ‘lead fulfilling lives with purpose, balance and meaning’—in other words, their quality of life,’ says lead author, Professor Rachel Ong ViforJ of Curtin University.

Precarious housing includes conditions such as facing forced moves, living in unaffordable housing or overcrowded housing as well as area-based settings such as living in an area of socio-economic disadvantage or in a higher crime area.

Forced moves and unaffordable housing stand out as being particularly strong drivers of a decline in wellbeing. Forced moves result in a decline of 1.6 per cent in the wellbeing index (which is based on a number of variables), while unaffordability depresses the wellbeing index by 0.8 per cent. Forced moves and unaffordability also depress the mental health score by 1.7 per cent and 0.5 per cent respectively. Neighbourhood conditions have an impact too, with, for example, satisfaction with one’s community being negatively affected by higher levels of neighbourhood hostility.

The research also identified that young people are more likely to fall into or remain in precarious housing than older people, with 19 per cent of people aged 25–34 years falling into precarious housing and 24 per cent staying in precarious housing from year to year. In contrast, only 4 per cent of the 65+ years age group fall into precarious housing and just 12 per cent stay in precarious housing from year to year.

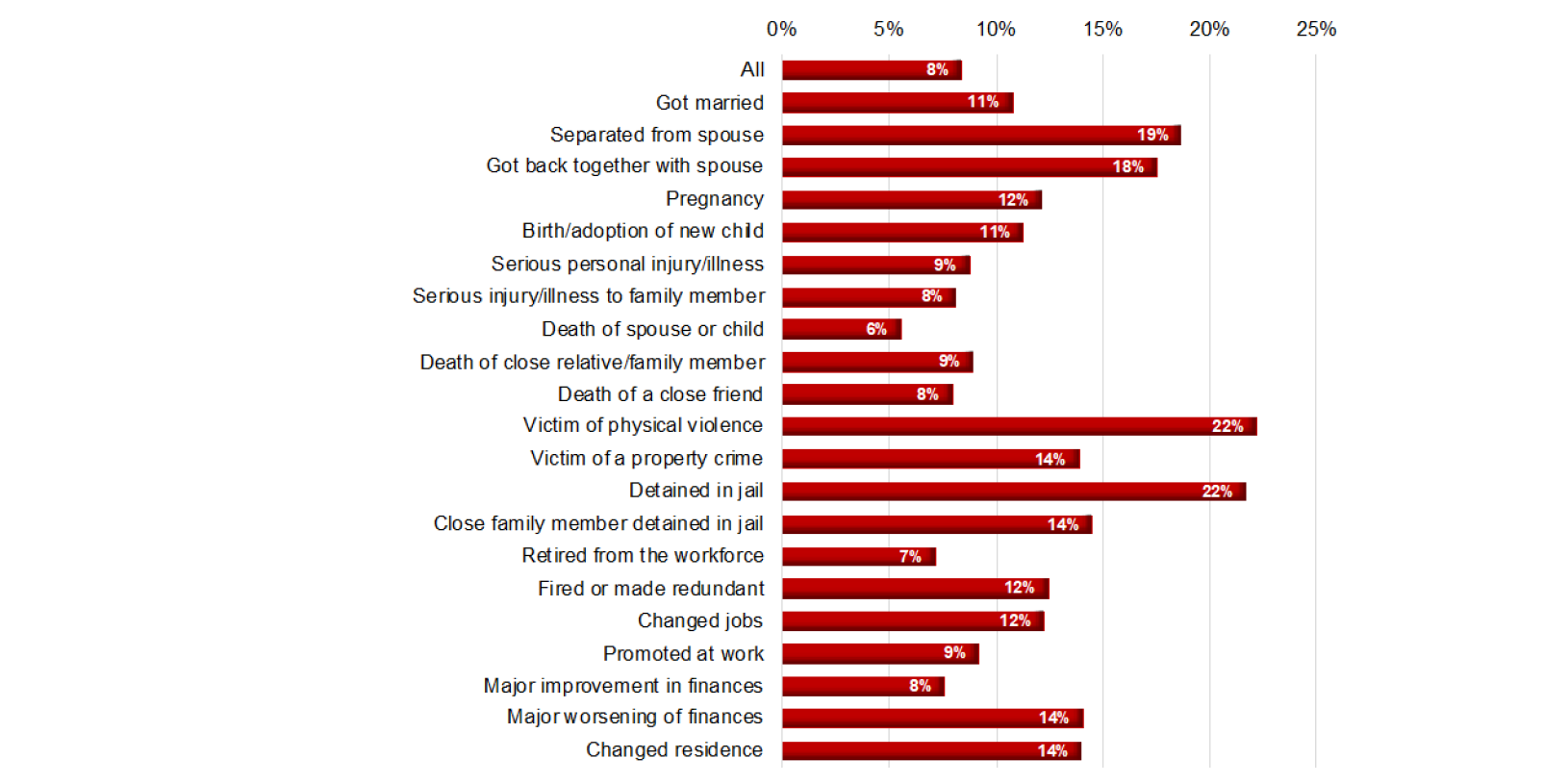

Figure 1: Share of those not previously precariously housed who fall into precarious housing and experience a major life event, 2002–2008

HILDA survey 2002–2018

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the research finds financial satisfaction to be a key influencer of wellness outcomes for householders; so, for example, the odds of experiencing a forced move, unaffordable housing and overcrowding are all reduced when financial satisfaction grows.

‘We find little evidence that housing assistance in its current form offers an effective means of improving the wellbeing of renters who are precariously housed,’ says Professor Ong ViforJ. ‘This finding is robust across alternative definitions of housing precariousness and is consistent across housing-assistance types. Therefore, there is significant potential for reforming housing assistance programs—both Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) and public housing—to increase their effectiveness in improving the wellbeing of precariously housed housing-assistance recipients.’

As the real value of CRA has fallen well behind rent inflation there is scope for improved targeting so that CRA entitlements more closely match the needs of different population cohorts. While over two-thirds of low-income private renters are assisted by CRA, one-third of low-income CRA recipients remain in moderate to very severe housing stress after CRA is deducted from their rents. Changing CRA eligibility rules to better align with housing need would offer the greatest benefits by reducing the numbers of low-income rental tenants in housing stress by 44 per cent while generating fiscal savings of $1.2 billion per year.