Tenant landlord relationship tested during COVID-19

New research examines mental and economic impacts on renters and landlords

12 Nov 2020

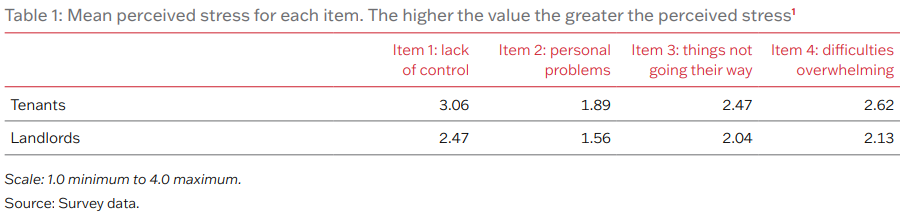

During the pandemic, over one-fifth (21%) of surveyed tenants felt that difficulties were piling up so high that they could not overcome them, compared to just 6 per cent of landlords according to new AHURI research. In addition, almost one third (32%) of tenants reported that they often felt they were unable to control important things in their lives, compared to 15 per cent of landlords.

The research, ‘Post pandemic landlord–renter relationships in Australia’ led by researchers from RMIT University, investigated the mental and economic wellbeing of landlords and tenants to help governments at all levels make the best housing policy decisions during and following the coronavirus pandemic. With the unemployment rate reaching over 9 per cent, landlords and tenants that have lost employment, had reduced income, or are looking for work, face a challenging financial situation meeting rent or mortgage payments.

‘Our analysis found that there was not a consistent way that negotiations played out. Some landlords were willing to consider financial assistance for their tenants but were unsure what evidence of hardship they could, or should, ask for. Without clear protocol on acceptable and unacceptable practices during negotiations, there was risk that the tension would not be resolved...’

While tenants largely believed the government support interventions such as JobSeeker and JobKeeper had been effective, to help reduce financial strains and issues relating to stress and mental wellbeing, there was confusion, stress and uncertainty about what would happen at the end of the government support period.

The research also reveals the tensions in negotiations between landlords and tenants during the pandemic. The majority of tenants had financial concerns due to the pandemic, but for many there was a hesitancy to ask the real estate agent or landlord for a rent reduction or rent deferral. This often related back to the uncertainty about the impact on their housing security, but also that there was the perception that landlords would be resistant to help and would cause further tensions and stress for the tenants.

It is clear that with a range of different approaches for landlords and tenants to raise and negotiate issues around rent due to changing financial circumstances from COVID-19, there was no common approach to how this was addressed.

‘Our analysis found that there was not a consistent way that negotiations played out. Some landlords were willing to consider financial assistance for their tenants but were unsure what evidence of hardship they could, or should, ask for. Without clear protocol on acceptable and unacceptable practices during negotiations, there was risk that the tension would not be resolved,’ said research lead author Dr David Oswald from RMIT University. ‘Many landlords reflected to us that during the pandemic everyone needed to be more accommodating and make sacrifices, and that they had a role and responsibility for the wellbeing of their tenants. This was not only about helping tenants, but also a reflection that receiving some money for rent was better than letting the property sit there empty, without rent, if the tenant had to move out.’

‘Those landlords who had resisted reducing rental payments seemed to come from concerns around their own financial position, such as the need to continue to service their own mortgages or for landlords who were retired.’

The report can be downloaded from the AHURI website at http://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/344